Quick Slant: MNF - A Wingnut and a Carriage Bolt

Mat Irby’s Quick Slant

There will always be a rivalry between the East and West Coast. It’s more than Lakers/Celtics or Tupac/Biggie; it’s Heffner/Hoffa, Gehry/Lloyd Wright, and Disney/Sinatra. It’s the stiff pragmatism of the Ivy League versus the drop-out tech cowboys of Silicon Valley. It’s Park Avenue spreadsheets versus Palo Alto vibes, Baltimore brick versus Santa Monica glass, Wall Street sharks gaming basis points versus crypto evangelists betting on code, and, of course, eight months of sunless winter versus year-round palms and sunshine.

The East Coast is America’s backbone. It was here that the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution were written—where the Boston Tea Party happened, Washington crossed the Delaware, and the Gettysburg Address was given—I Have a Dream, Ask Not What Your Country Can Do, and Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death. It was land built on bruised backs, coal dust, and blood-calloused hands. The robber barons hailed from oil, coal, and steel, becoming symbols of a new Bronze Age. Self-made, they rose to heights rarely seen in human history, accountable only to themselves.

To the East Coast, even now, there’s a sense of entitlement about the head start they gave America. They may not admit it, but to them, the West Coast pencil-neck geeks, Hollywood elites, and trust fund babies owe them everything. Even the movie camera was invented by Thomas Edison in New Jersey, then exported to the Hollywood Hills—a stolen industry, made identity, forged by East Coast élan. The East Coast innovation is practical and long-lasting; the West Coast's fleeting and empty—a distant Rome, all play with no elbow grease.

Yet the West Coast claims its own ingenuity. Its framework is more than Hollywood: it’s code, online shopping, and fiber optics. This is their era; the wealthiest CEOs no longer trade in brick-and-mortar but in AI and microchips. They usher in the future, creating our most prized possessions—cell phones, streamers, and social media accounts.

California knows the rest of America reduces it to squishiness without brawn; but that is to overlook its less famous, but very real blue collar: the cold, oil-stained hands of longshoremen stacking the world’s freight, the roughnecks on the Central Coast’s faded oil derricks, the sailors of San Diego or marines of 29 Palms, and the vast, anonymous host of service workers—the maids, janitors, and kitchen staff—who keep the whole sprawling illusion running.

The Eagles play tough. Their most famous play is a scrum where 2,000 pounds of men push slowly against 2,000 pounds of men, and their QB epitomizes Resilience Development, having failed and been written off many times but getting back up and applying himself to post-traumatic growth until he held Lombardi... twice. Their most famous player over the last decade is a center with a lumberjack beard; their emphasis as a team is always on the trenches.

But the Chargers play tough, too. It’s easy to misconceive about a team calling a gilded glass palace like SoFi, the most expensive stadium in history, home. But their HC, Jim Harbaugh, is a Toledo man—a Michigan Wolverine, a Chicago Bear, “Captain Comeback.” His football is far more analog than digital; his upbringing as the son of a veer/power option coach, a disciple of Schembechler, set the stage for what he would value most: the trenches, the running game, and disciplined fundamentals.

So, when they meet Monday night, it won’t be the conventional dichotomy we want to imagine. It will be two analogs, dressed in different garments—a mirror match between two identical souls wearing different cultural masks. A wing and a lightning bolt atop their crowns mislead us; more like a wingnut and carriage bolt. And their playoff lives are in doubt. When the edges start to close in, the cornered reveal themselves: conquerors or casualties; these moments are the arbiters of eternity that cast champions into the stars.

The reeling stops here; this is the moment when one finds the more to give that no one else knew they had.

Chargers

Implied Team Total: 20

A pair of 8-4 teams, the Chargers and Eagles, would each be in the postseason tournament if it started this week. But there is also a foreboding sense that certain undercurrents could be gathering to sweep them away.

Of the two, the Eagles feel safer because their competition for a division crown has been lighter than expected, especially after the Lions dismantled the Cowboys last Thursday. With the Giants and Commanders already out of the math, it should feel like cruise control time for the defending Super Bowl champions, who now have a 2.5-game lead, and yet, somehow it doesn’t.

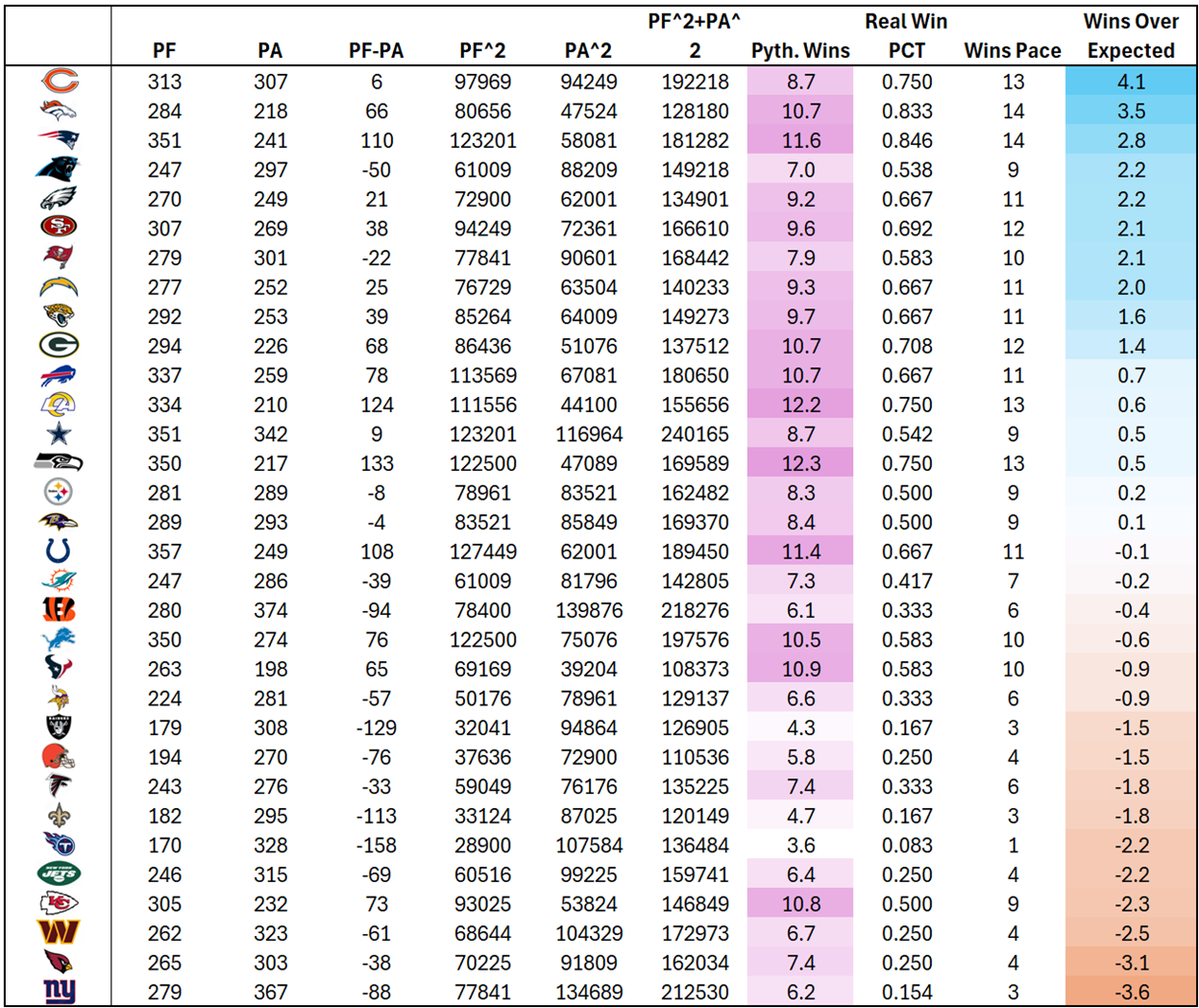

The Eagles have lost two in a row, and their offense has been in dysfunction for more like a month. Alarm bells are ringing, and even if the Eagles, who have overachieved by 2.2 games according to Pythagorean expected wins, can make it to January, there are significant issues to work out. As such, they are a team desperate to check the king on Monday, as a win against LA would make a fall from grace far less likely.

As for the Chargers? They are on a white-knuckle ride, as they were a year ago. They are two wins over expected, themselves. Catching the Broncos for the division seems unlikely, but a wild card is in reach.

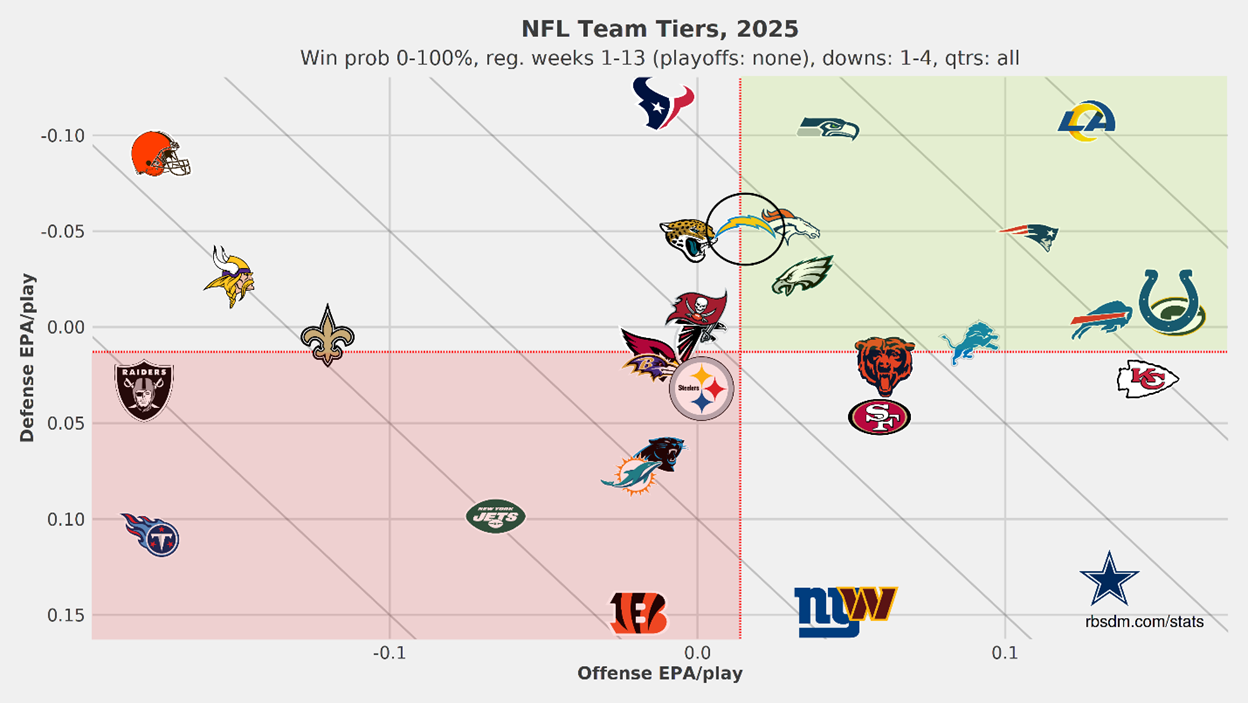

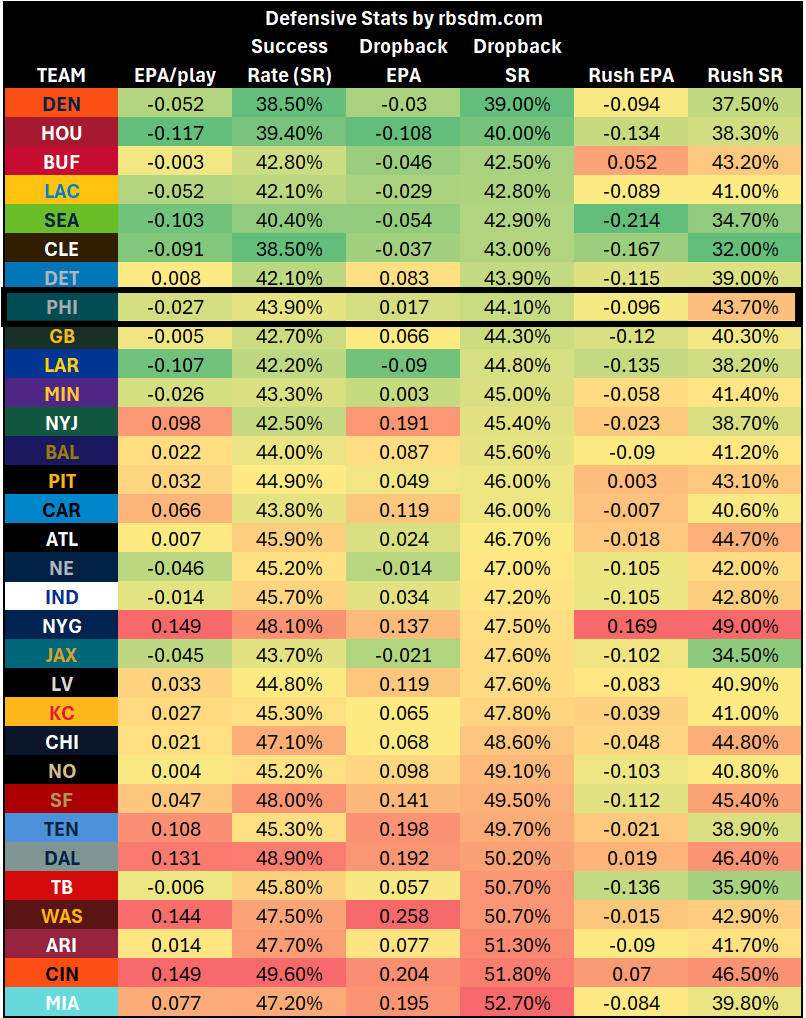

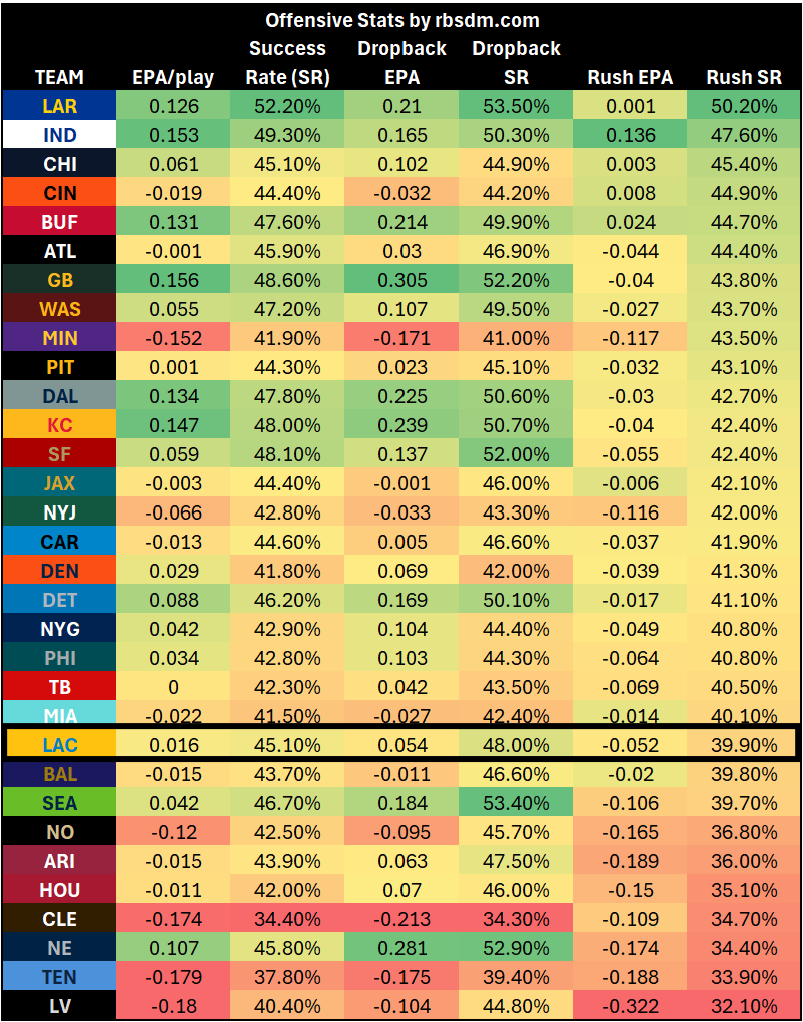

The Chargers’ offense is about average in EPA, but their defense is well above average.

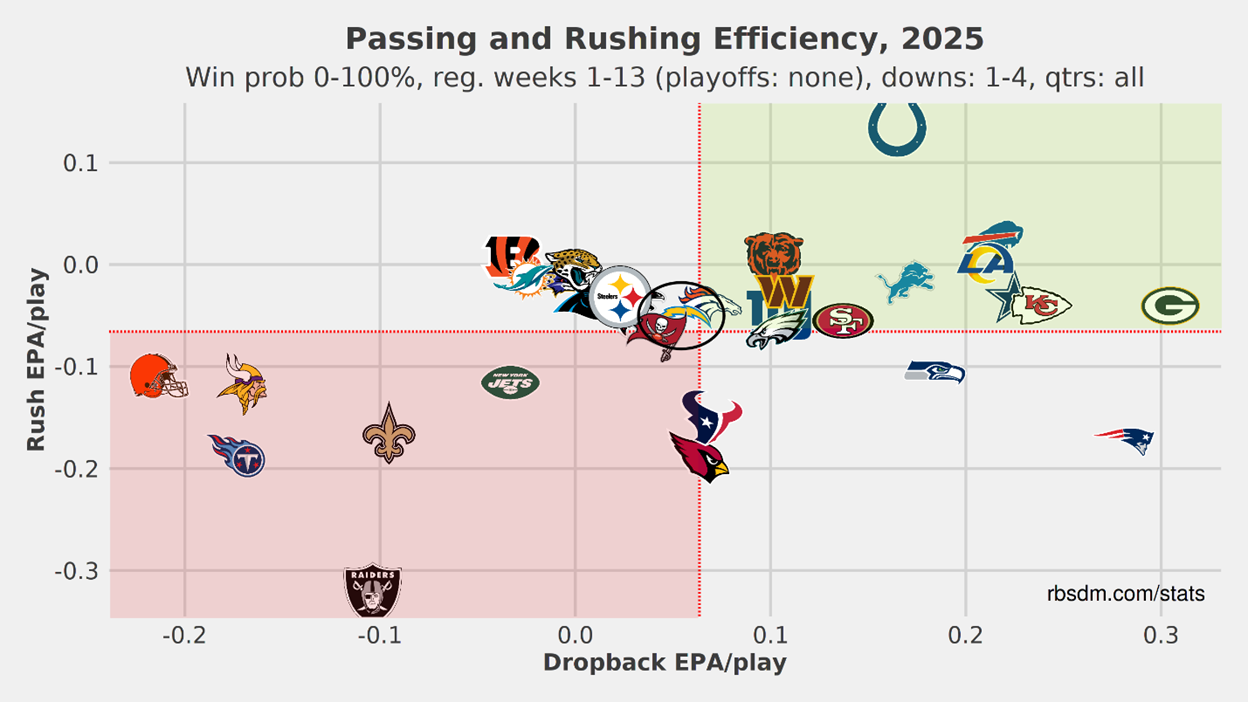

In terms of EPA, they are about the same, whether running or passing—pretty much right in the middle of the pack.

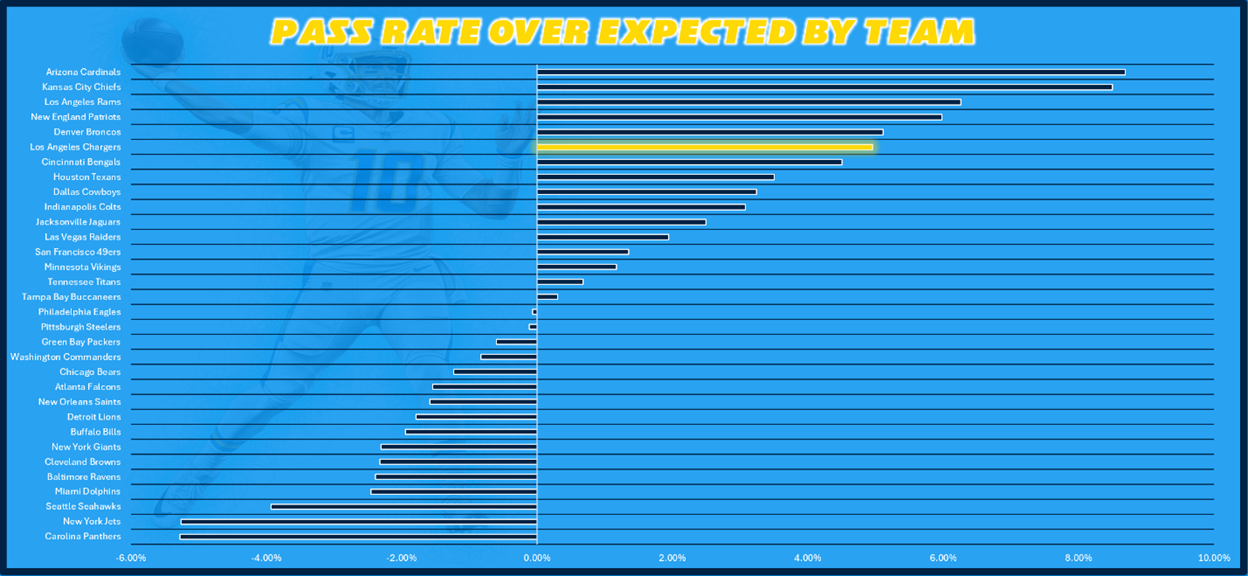

The standard narrative entering the season was that the Chargers would be unbearably run-heavy, but their pass rate has been 59% (T-11th). They do operate slowly on offense, getting offensive snaps off in an average of 28.1 seconds to snap (T-28th). They have been ahead by seven or more on 248 offensive plays (T-4th), and when leading by that much, they drop to a 42% pass rate. This drastically reduces their gross pas rates, making it appear that running is far more of a default than it actually is. In reality, they have a pass rate over expected (PROE) of 4.6% (6th). The Chargers get off 67 plays per 60 minutes (6th).

The Chargers rank 16th in offensive EPA per play and 14th in offensive success rate. They rank 18th in offensive EPA per dropback and 12th in offensive success rate on dropbacks.

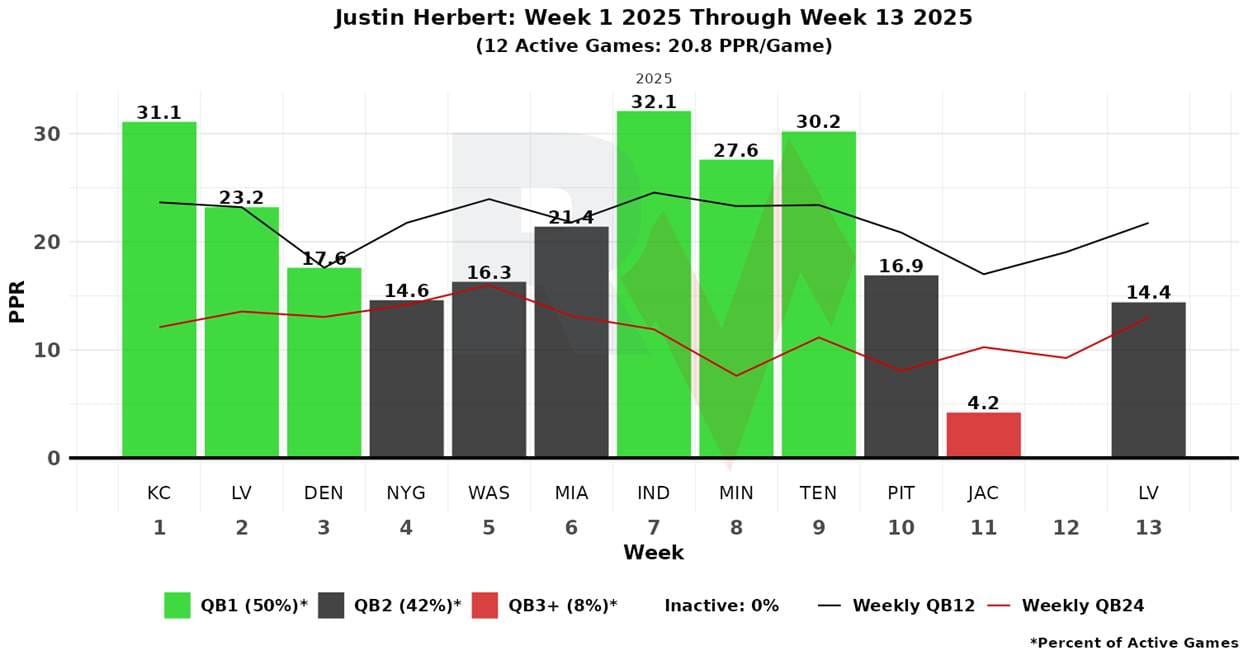

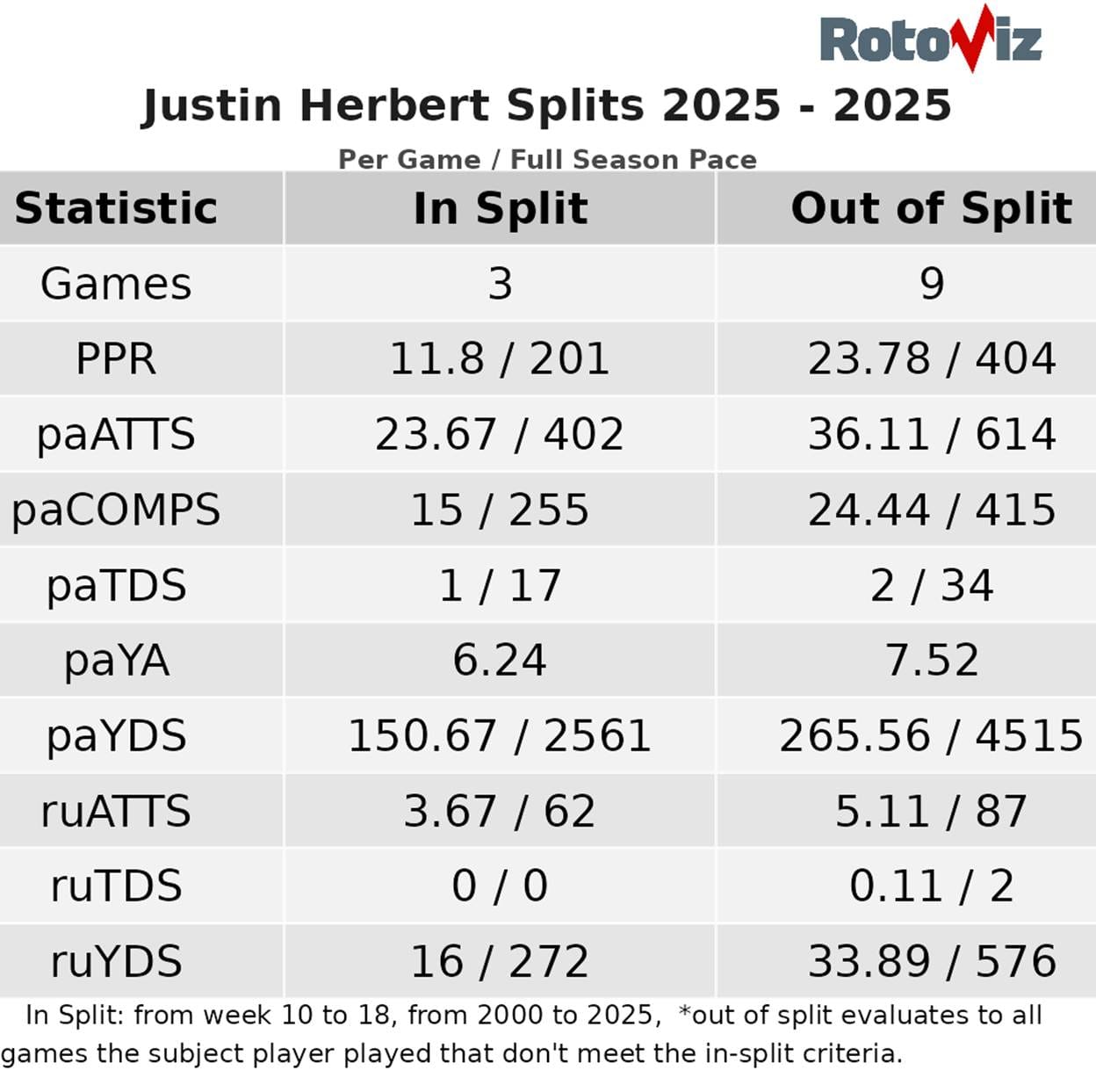

They are led by QB Justin Herbert, who had surgery to repair a fracture in his non-throwing hand this week. Herbert started the season as one of the more reliable fantasy QBs in the game, hitting QB1 thresholds in six of his first nine games and never falling out of the top 24. Since Week 10, however, there has been a distinct sea change, and Herbert has been a middle to low-end QB2 or worse in all three of his games.

Ultimately, Herbert had 41.9 dropbacks per game (2nd) and 36.1 pass attempts per game (5th) in Weeks 1-9; in three games since, he’s had 29.7 dropbacks per game (31st) and 23.7 pass attempts per game (32nd). This is a massive shift, and every counting stat will suffer dramatically as a result. Additionally, his fantasy points per dropback have fallen from 0.52 during the first nine weeks to 0.37, so it isn’t only volume; it’s also efficiency.

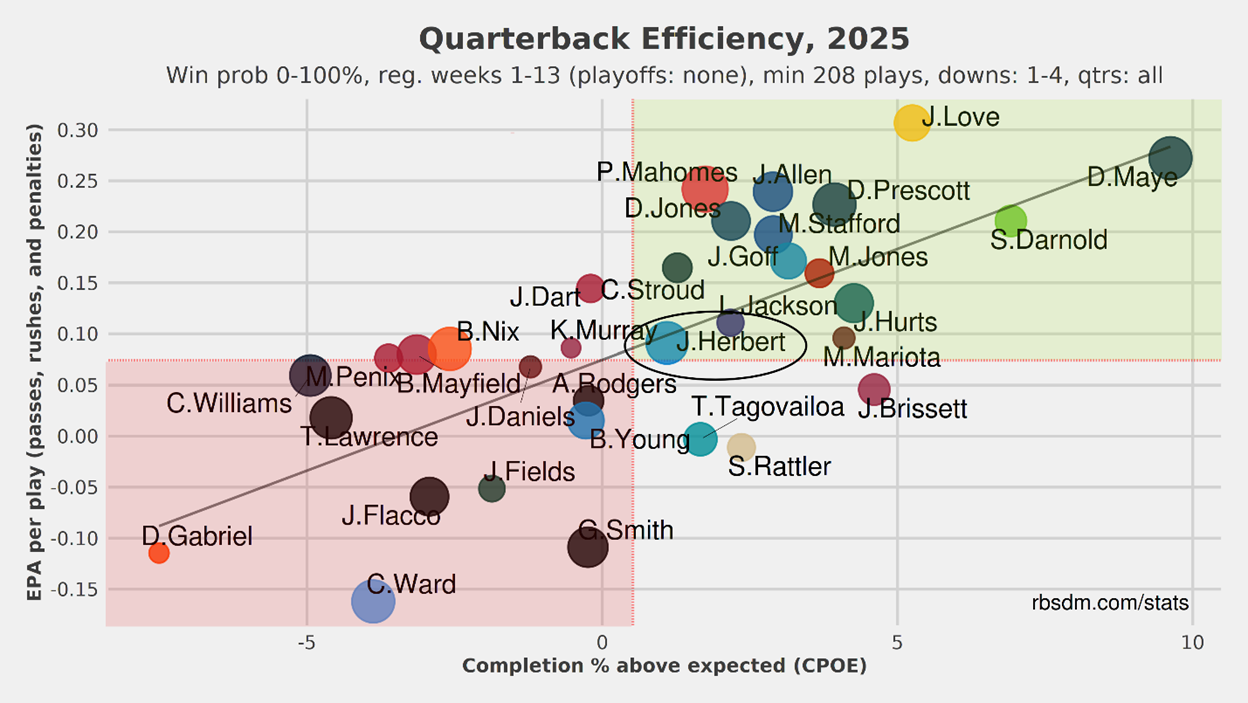

Herbert has a good rushing platform. He has 32 scrambles (5th) for 311 scramble yards (4th). He has 57 total rushing attempts (T-7th) for 353 yards (3rd). This gives him a head start that raises both his floor and ceiling. As a passer, he is above average in both EPA and CPOE.

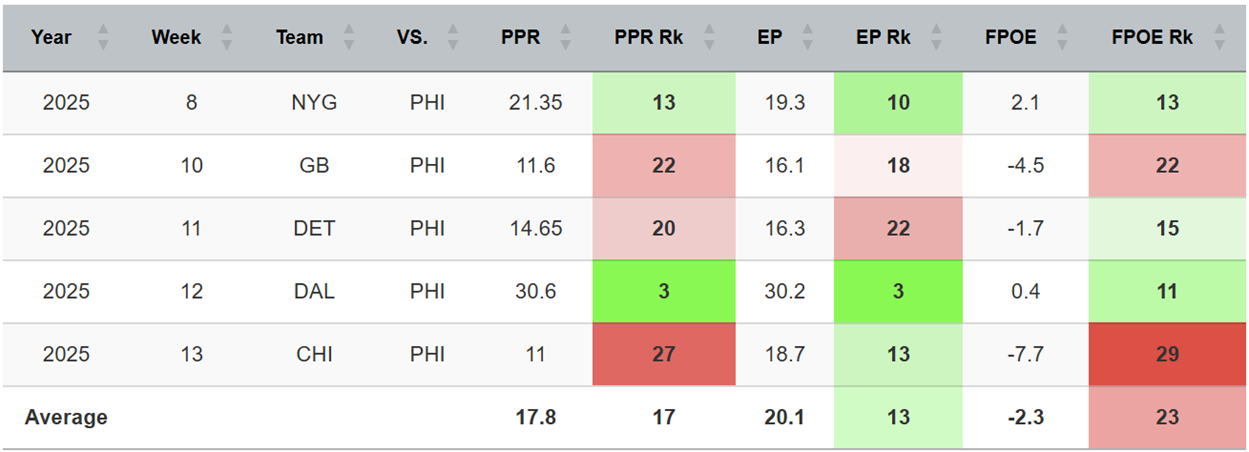

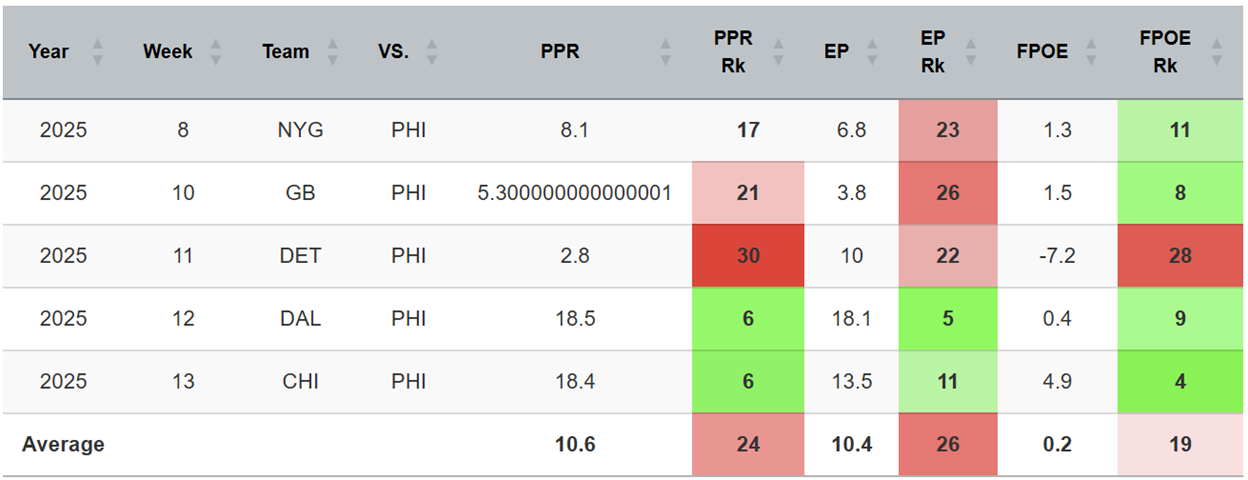

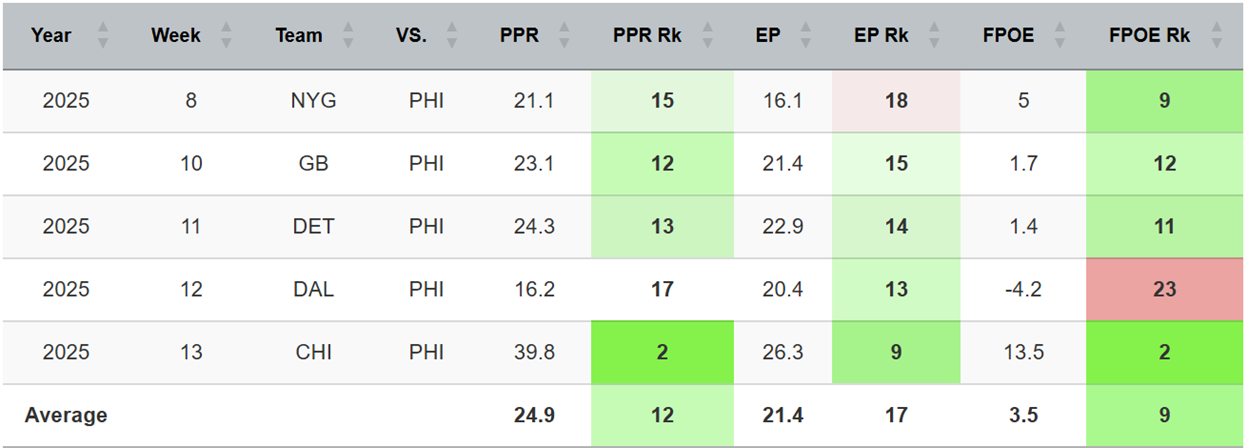

The Eagles have been about neutral of late against fantasy QBs, surrendering the 17th-most fantasy points to opposing QBs in their last five games.

They have surrendered more expected points (EP) than fantasy points over expected (FPOE) relative to average. This is not uncommon with teams that front-run; they typically face more passes from desperate teams trying to get back into games, and they are generally more fortified against the pass because they know it's coming. Philadelphia has spent 223 offensive snaps this year with a lead of seven or more (9th), so this checks out.

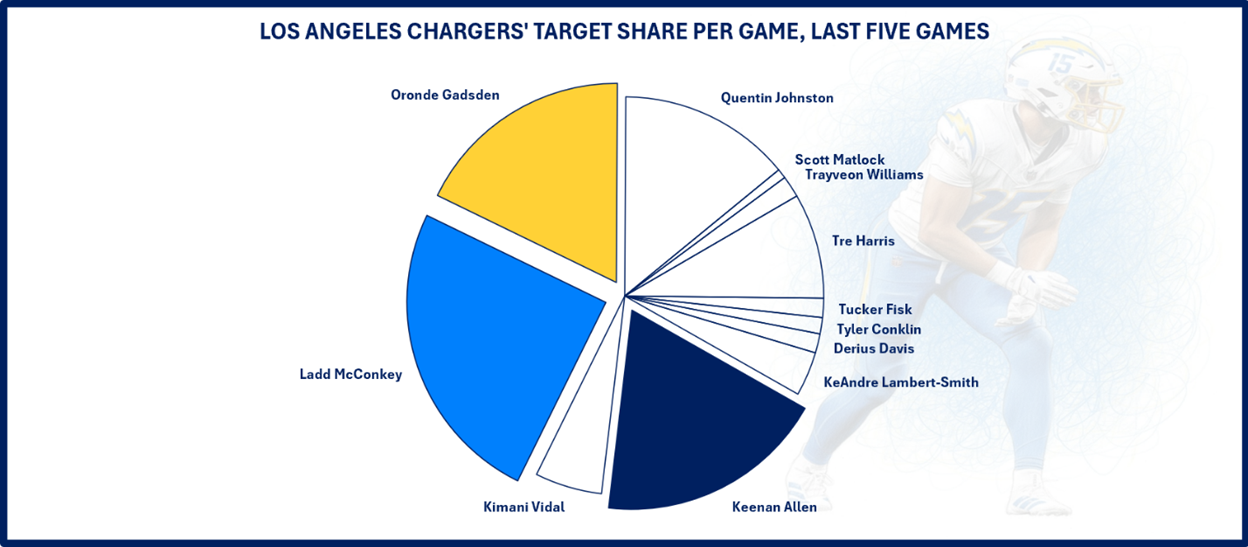

The Chargers have three players with a target share per game rate of at least 15% in their last five games: WRs Ladd McConkey (23.9%) and Keenan Allen (17.9%), and TE Oronde Gadsden II (17.2%). Quentin Johnston (13.4%) is above that threshold for the year (17%), but he’s taken a less significant role recently.

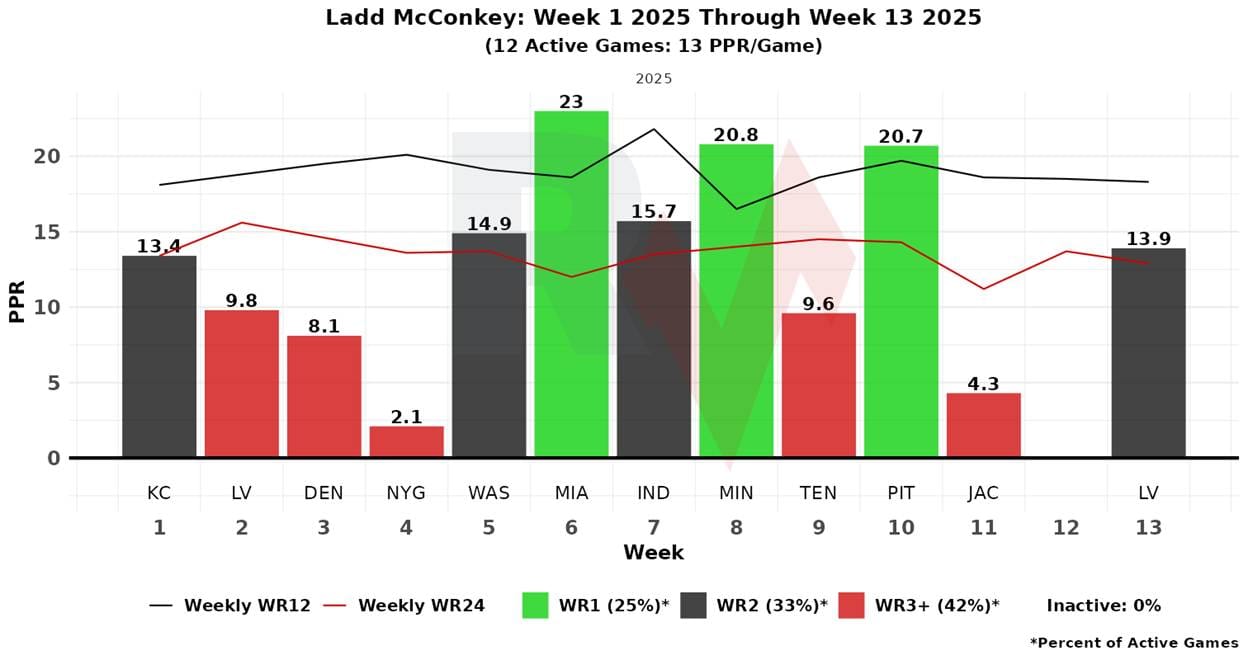

All of the Chargers’ pass-catchers, as we analyze their game-by-game breakdowns, will falter as Herbert has over their past few games. McConkey had his strongest run from Weeks 6-10, where he logged three WR1 weeks.

McConkey’s red flag coming into the year was that he was not used as an end zone target; this year, he has nine end zone targets (T-9th). He has a lot of strong rate and per-route metrics; the Chargers having four legitimate pass-game targets has hurt McConkey’s raw volume, especially as Herbert’s dropbacks have taken such a steep downturn.

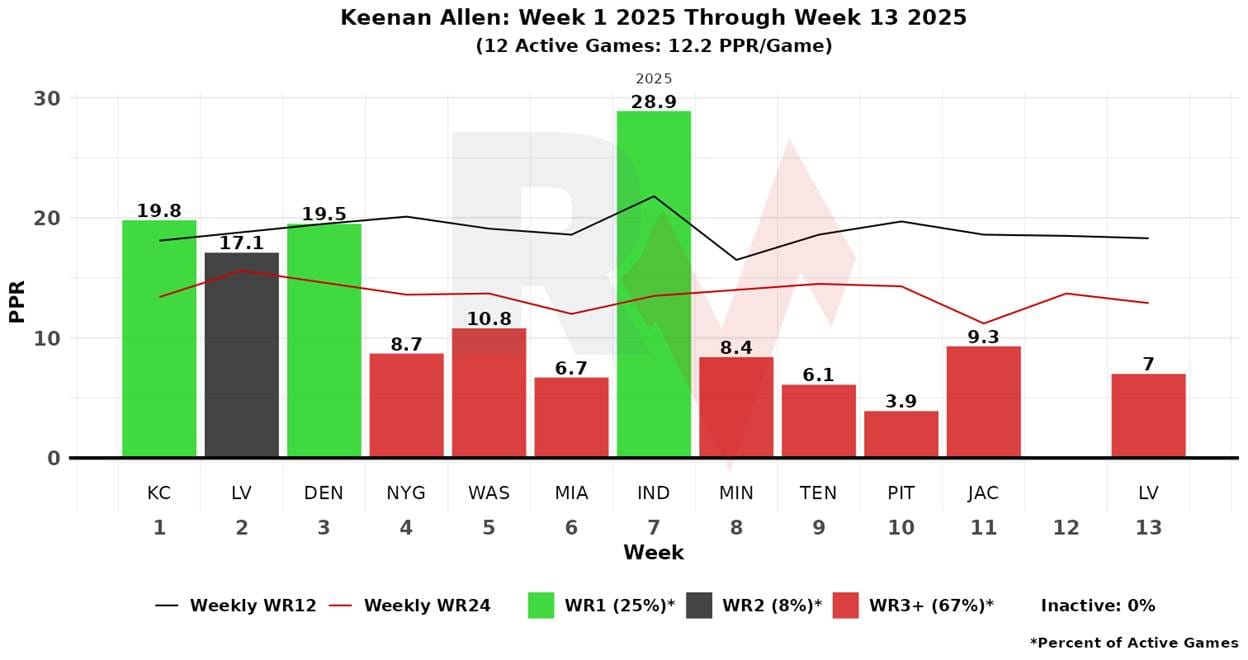

Allen came out of the gate like gangbusters, flirting with 30% target shares in his first three games; he has been a far more tepid fantasy chip ever since. From Weeks 4-13, Allen has recorded only one WR1 week—a blowup game against Indy in Week 7—and otherwise, has not even finished in the top 24 in PPR. He is verging on unusable, although in deep PPR leagues where five or more WRs can be used, including flexes, he’s still a good option.

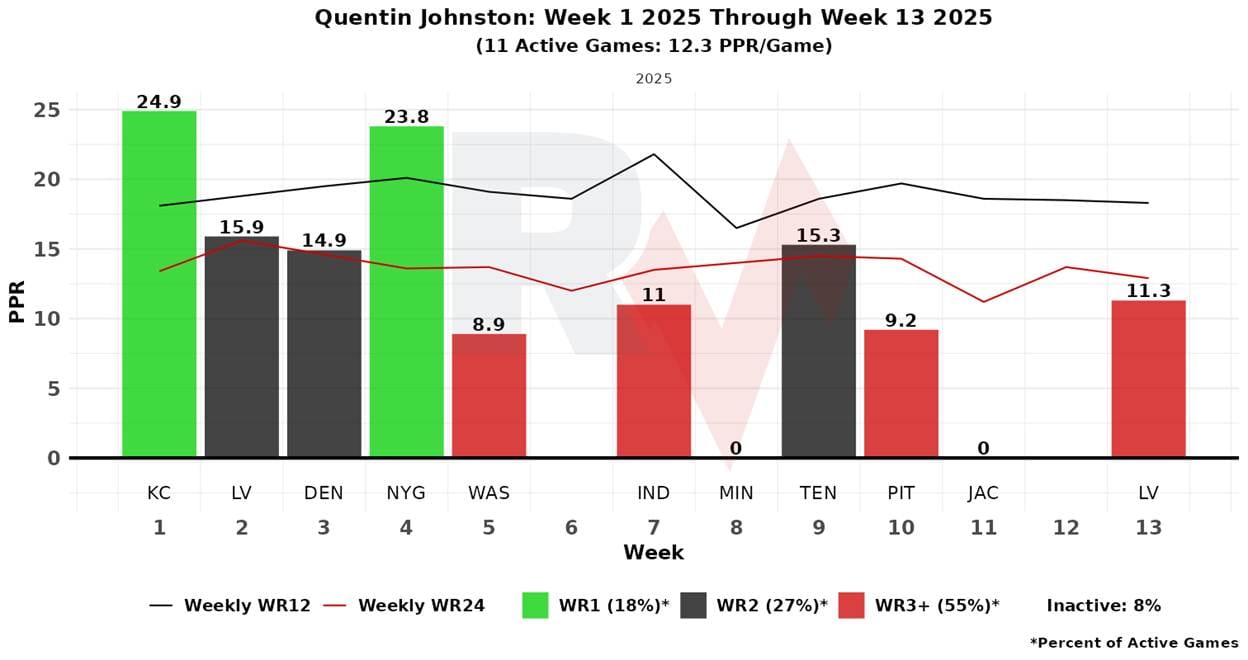

Johnston also started incredibly strong, looking at times like the Chargers’ WR1 through the first four games. Same as Allen, his production has fallen off ever since. For Johnston, his usage changed from an intermediate role to a more vertical one; with that, there is expected volatility. We have seen the downside, as he’s posted a couple of goose egg weeks; we haven’t really seen the upside of a multi-TD game, or big, breakaway yardage, since this shift.

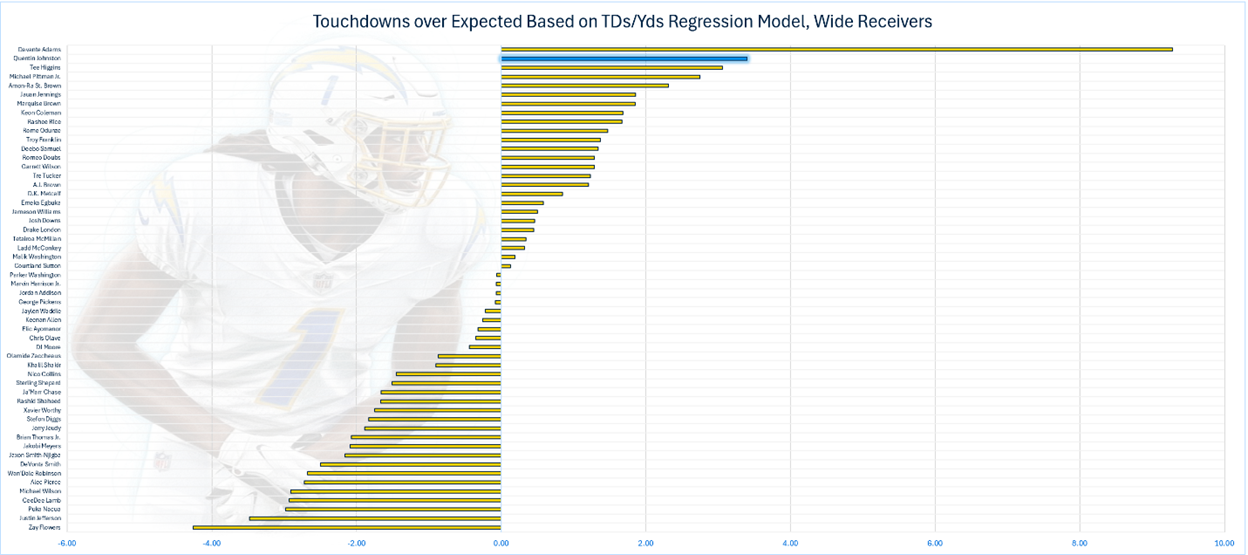

Johnston has become incredibly TD-dependent; he has used TDs to reach respectable fantasy totals in Weeks 7, 9, and 13 (and even then has not cracked the top 12). This, in combination with the fact that, based on TDs/Yds, has the second-most TDs over expected, trailing only Davante Adams, and has to be viewed as a TD-regression candidate. Based on his current usage, if Johnston is expected to score TDs at a lower rate going forward, he can’t be played in managed leagues.

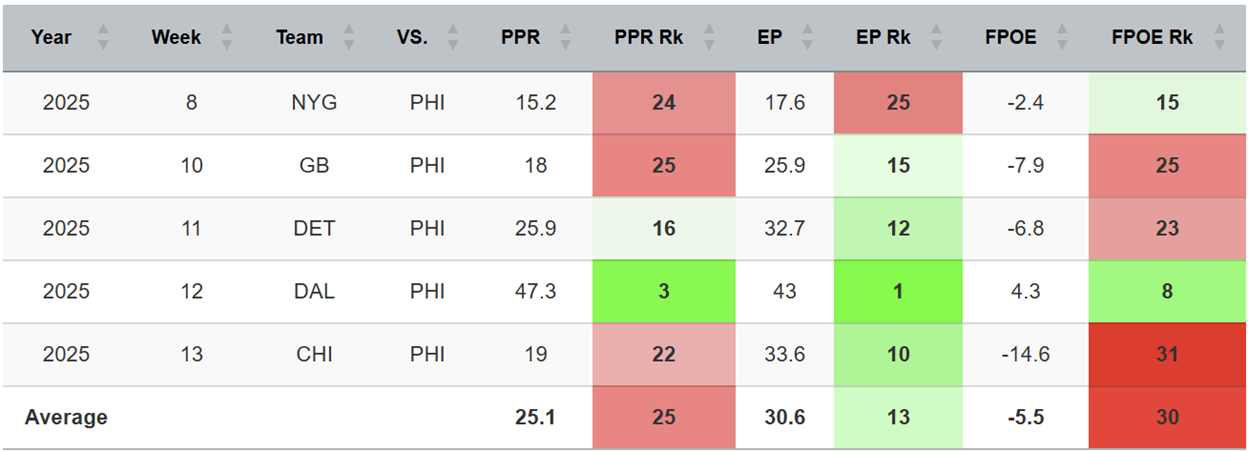

To complicate matters of decreasing volume and a lot of target competition, the Eagles present a formidable matchup for WRs, surrendering only the 25th-most fantasy points to opposing WRs in their last five games. We see the same pattern as we did at QB: higher EP and lower FPOE.

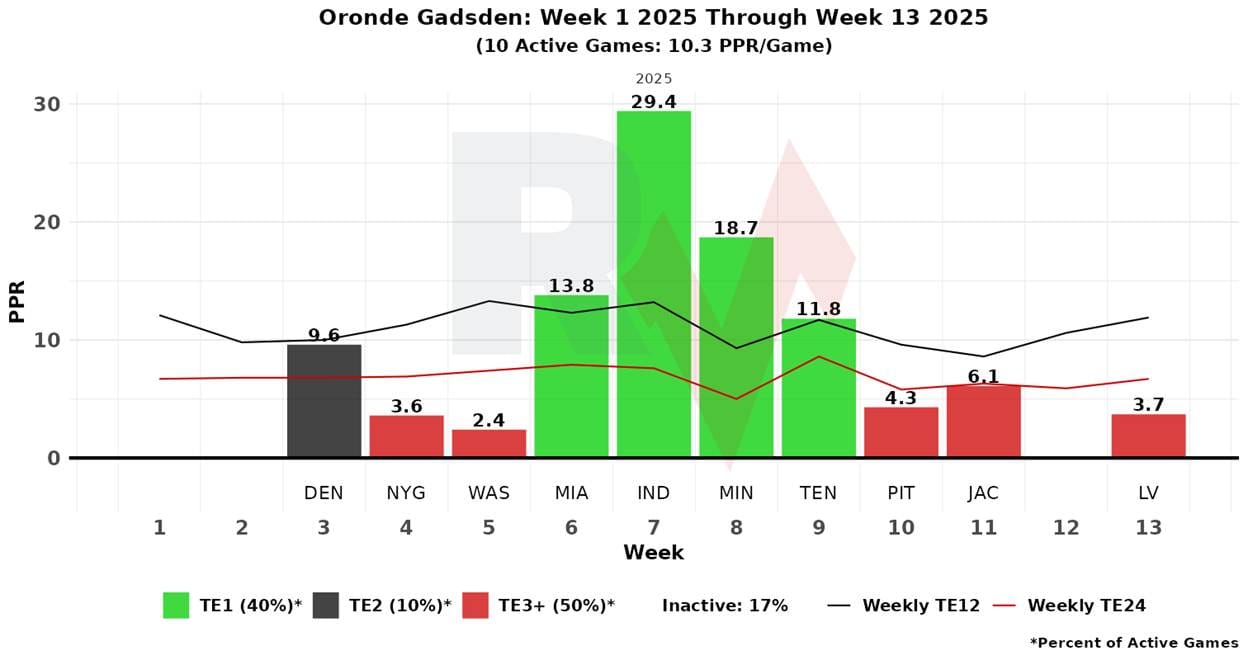

For a while, the rookie TE Gadsden seemed like a revelation, logging four straight TE1 weeks, including a massive output in Week 7 against Indy. His last three appearances have been disappointing, but they have directly correlated to Herbert’s low output games. Suppose we accept the possibility that Herbert’s downturn is somewhat random (which we don’t know, but it definitely could be). In that case, there is less cause for concern about Gadsden, as he will probably see a corresponding rise if Herbert bounces back.

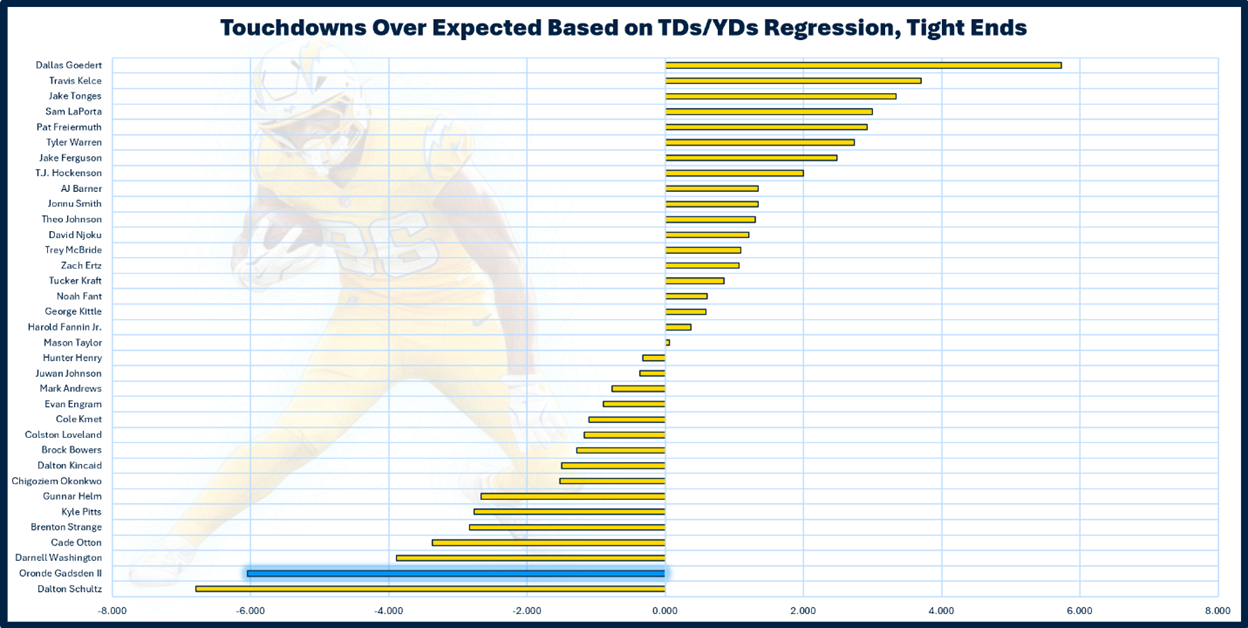

Also, unlike someone like Johnston, Gadsden profiles as a significant positive regression candidate based on TDs/Yds, where he has scored about 4 TDs below expectation. If we expect a higher rate of scores as we advance, and, more importantly, Herbert can reclaim some modicum of his early-season usage, Gadsden could easily climb back into the TE1 sphere. There are a lot of ifs, and I’m not sure if that should translate to plugging him in lineups this week, but he’s worth a hold if you do not have a blue-chip TE.

As they are in the passing game in general, the Eagles are tough on opposing TEs as well. They have surrendered the 24th-most fantasy points to TEs in their last five games.

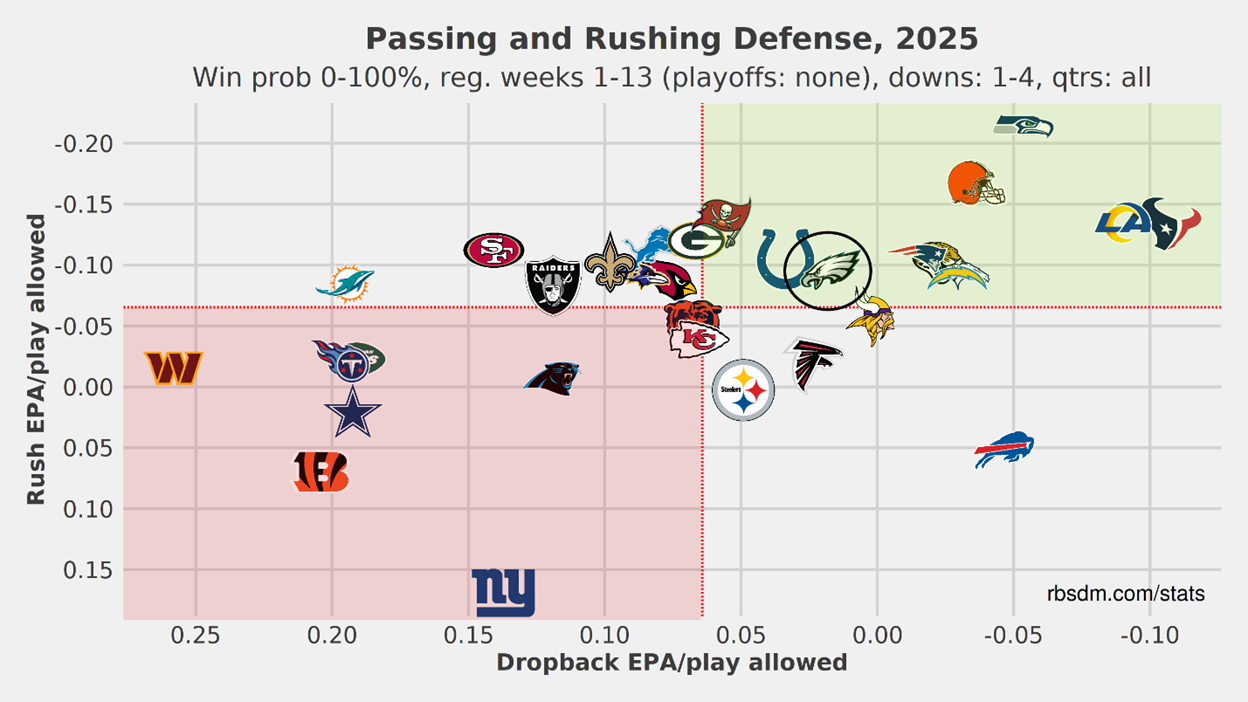

The Eagles’ defense is above average in dropback EPA and rush EPA.

They rank ninth in EPA per play allowed and 14th in defensive success rate. They rank 11th in EPA per dropback allowed and eighth in defensive success rate per dropback.

The Eagles run zone coverage on 67.2% of their plays (21st) and use two-high safeties on 50.2% of their plays (12th). Their most common alignments are Cover 3 (27.5%), Cover 1 (21.7%), and Cover 6 (22.1%), which they run more than any other team in the league. They blitz at a rate of 20.6%, which is well below average.

Fantasy Points’ coverage matchup tool assigns a zero-based matchup grade to each pass-catcher based on their opponent’s use of specific types and rates of coverage and how that pass-catcher performs against them. Positive numbers indicate a favorable matchup and negative numbers indicate an unfavorable one.

Based on this, Allen (+3.4%) and McConkey (+0.8%) have slightly favorable matchups, while Johnston (-4.1%) and Gadsden (-8.7%) have slightly unfavorable ones.

PFF’s matchup tool is player-based, pitting the PFF ratings of individual players against each other for an expected number of plays based on historical tendencies and rating on a scale from great to poor.

Based on this model, Allen again pops with a good matchup, while McConkey, Johnston, and Gadsden’s matchups all grade out as fair.

The Chargers are famously without both of their stud OTs: Rashawn Slater, who has been out all year, and Joe Alt, who was in and out but is officially lost for the year. Jamaree Salyer and Trey Pipkins fill in. Both rank outside of the top 50 according to PFF OT grades.

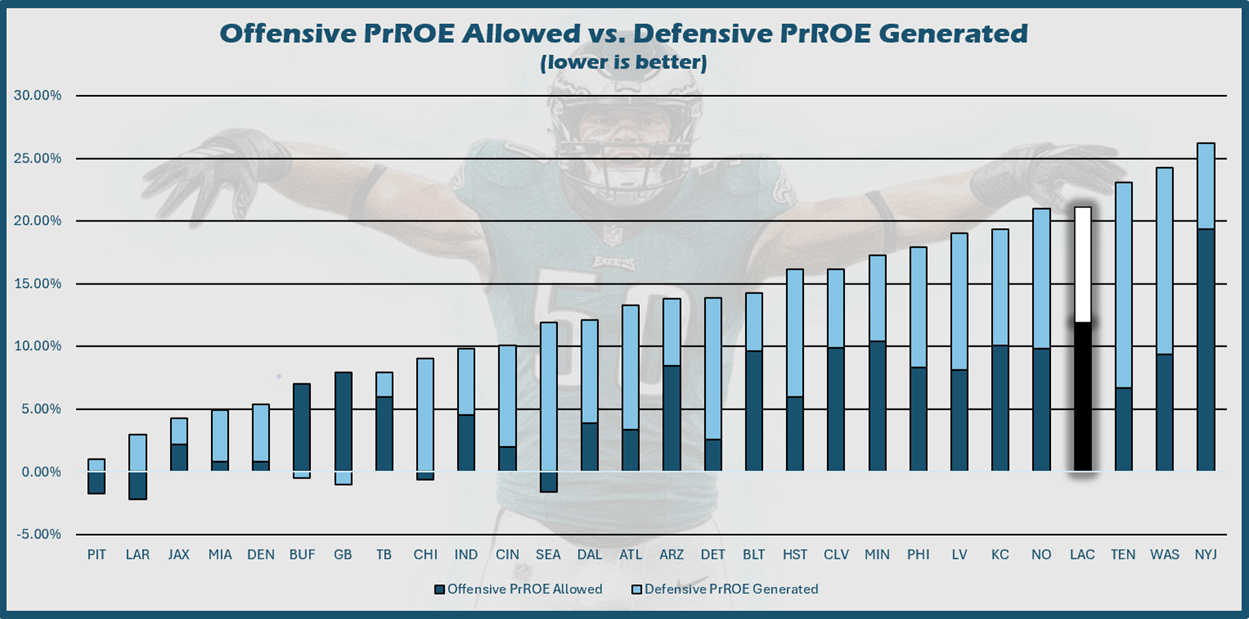

This has been a significant problem for Los Angeles, which allows an 11.88% pressure rate over expected (PrROE, 2nd of 28 Week 14 teams). Meanwhile, the Eagles generate 9.22% PrROE defensively (11th); the composite gives LA the fourth most disadvantageous pass-blocking situation of the week.

It should be noted that the Eagles will be without their superstar DT, Jalen Carter, who is out with injuries to both of his shoulders. Carter has performed better in the pass rush from the defensive interior than he has in the running game in 2025, though his absence should be felt in each area.

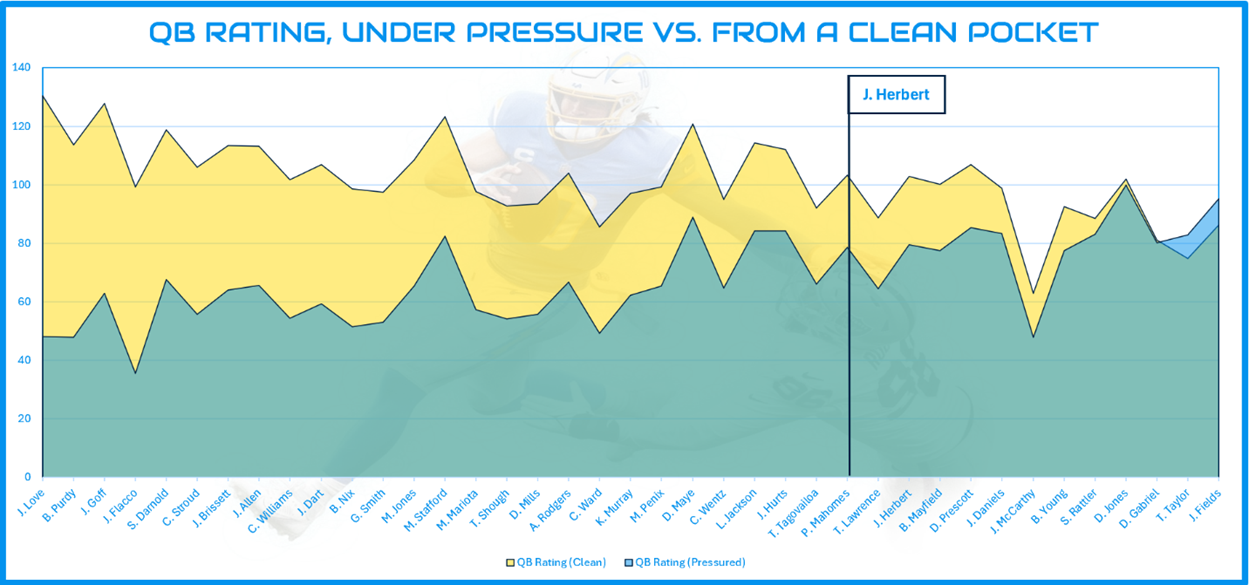

Justin Herbert has handled pressure well. Not only is he prone to scrambling successfully when under duress, but his QB rating drops only 23 points when under pressure vs. from a clean pocket (29th).

The Chargers’ run blocking unit generates 2.02 adjusted yards before contact per attempt (adj. YBC/Att, 16th). The Eagles’ defense allows 1.95 adj. YBC/Att (13th). This is nearly a push, so there is no real advantage for either team in this area when the Chargers have the ball.

The Chargers rank 19th in offensive EPA per rush and 23rd in offensive success rate on rushes.

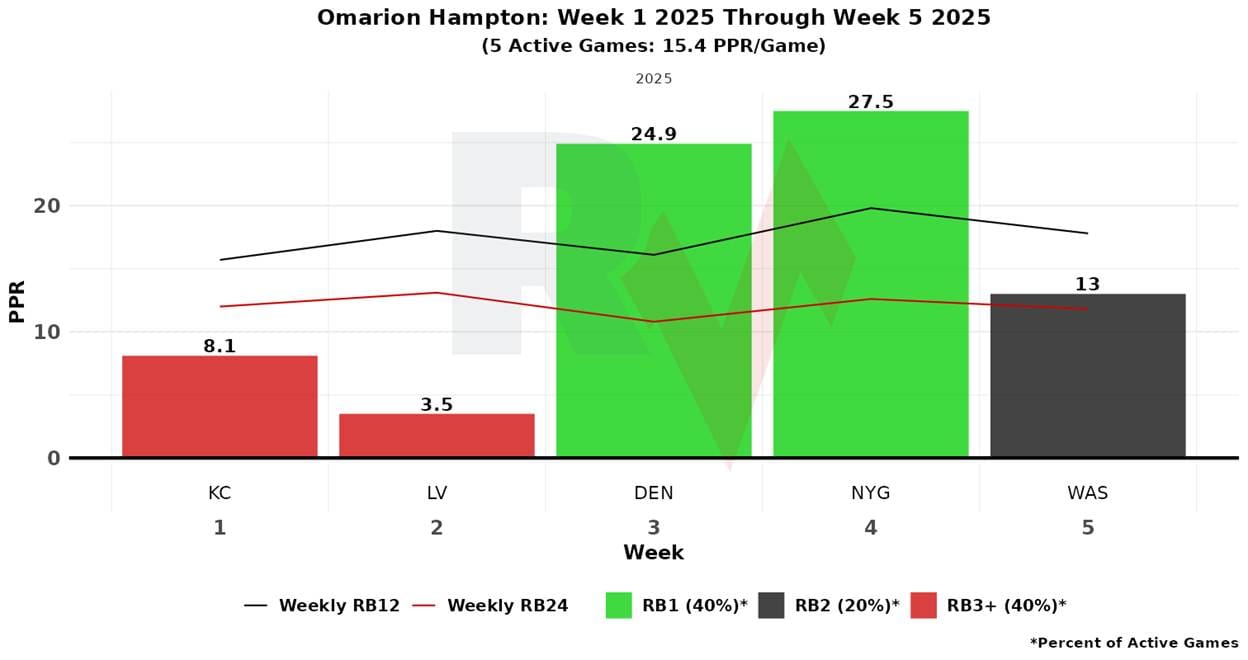

Adding to the team’s overall injury attrition—an annual tradition for LA, it seems—the Chargers have been down three RBs of late, first losing veteran RB Najee Harris (torn Achilles), then rookie RB Omarion Hampton (fractured ankle), and finally, contributing role player/special team RB Hassan Haskins (hamstring). This has left RB Kimani Vidal as the last man standing, and he has admirably filled the role for the most part, but the Chargers undoubtedly relish getting their first-round pick, Hampton, back this week for the first time since Week 5.

Hampton really only had two chances to be the Chargers’ lead back, and he shone in each, scoring in the 25-30 PPR-point range.

Hampton should have a chance to consolidate most of the backfield work in LA. This could lead HC Jim Harbaugh and OC Greg Roman, who have historically been run-heavy, to run more frequently. This is purely speculation.

Philadelphia ranks 13th in EPA per rush allowed and 26th in defensive success rate on rushes. This means they are at least somewhat prone to preventing big plays, but they can be chopped up one bite at a time.

There is obviously a tension between using Hampton with confidence, as injured players are often ramped up after long absences, or they are subject to reinjury. However, there is also an opening for an effective running game to potentially smash. What you trust to happen, or what risk you are willing to tolerate, is a matter of personal taste, but considering the potential upside, it is hard to sit out Hampton.

Factoring in extraneous factors like Herbert’s health and the fact that the Chargers are road dogs, I would be optimistic that the Chargers try to establish the run.