Quick Slant: Saturday Edition - Sentiment Gives Way to Modern Consequence

Mat Irby’s Quick Slant

Stepping off the Northwestern Elevated Line at the Wilson station, your foot would clunk over wooden planks bolted to a riveted steel skeleton suspended some 16 feet above Wilson Avenue. You’d head south toward Broadway and the headhouse, utilitarian and cold, made from unfeeling metals (the terracotta accents that would later define its aesthetic were not added until 1923). The skyline had yet to fill with glass and steel stretching toward the clouds; sunny blue skies hovered over buildings two or three stories tall, midrise at most, and the crisp wind smelled of coal.

It was a Sunday, so the shops were closed in this normally always-on commercial hub, among the fastest-growing arteries of an early metropolis. But today there was more bustle than usual. A buzz floated in the air as men in wool and women in fur moved south down Broadway, some on foot, by trolley, by car, or in a few remnant horse-drawn carriages. Locals knew to cut over to Clark Street, which would soon open to the main gates at Clark and Addison. You’d have to dodge a few more puddles, but the route was more direct.

As you drew nearer, the crowds thickened, and it began to feel like something special lay ahead. Then there it was, 56 feet high, steel and concrete, thin white arches spread like arrow slits in the walls of some modern castle. You sensed it first through the narrow sightlines between buildings, and as you approached, its sheer size became exhilarating.

Mere months ago, player-coach George Halas had moved his Decatur Staleys to Chicago (a year later, they would be rebranded as the Bears), the third-largest market in the United States, and secured the rights to use Cubs Park, which would come to be known as Wrigley Field. The crowds they drew—more blue collar than horse races or baseball games—were massive: five, six, seven thousand people—proof of concept for the fledgling NFL.

For the visiting Green Bay Packers, this was a monumental leap in scale. Back home, they played before modest crowds, at most half this size. For the roughly 7,000 in attendance on a late-November afternoon, there was no way of knowing what significance the day would hold. The first chapter of football’s most essential rivalry was written here. Two legendary figures, Halas and the Packers’ Curly Lambeau, also a player-coach, tested themselves against one another—each serving as architect and laborer for a sport still under construction.

No one could have known the game they were watching would become America’s favorite and attain worldwide reach. They couldn’t imagine stadiums holding 70,000 fans, or a magic box in every home that would beam the game live from coast to coast.

To them, it was an affordable ticket, a way to pass a Sunday afternoon. It was a 45-yard run by Pete Stinchcomb; Halas catching a touchdown; Chicago’s Tarzan Taylor breaking Cub Buck’s nose, which bled like hell. And in the end, their hometown team shut out the Packers, 20–0, business as usual for one of the NFL’s earliest premier franchises.

But the Packers improved quickly, emphasizing the pass, a sharp contrast to Halas’ T-formation. Through the late twenties and thirties, they survived the Great Depression together. They traded punches, each winning their share of 12 championships, including two against each other in 1941 and 1944. They grew the NFL’s brand and filled the Hall of Fame with names like Nagurski, Grange, and Luckman. The rivalry was shaped as much by contrast—small town versus big city, competing styles—as by similarity—Midwestern roots, legendary player-coaches, perennial contention.

Today, the Packers and Bears have met 211 times, more than any other pairing, and the rivalry is widely regarded as the NFL’s most significant and historically relevant—known simply as The Rivalry because, when it started, a brand so simple was still available for the taking.

The Bears boast 39 Hall of Famers, the most in league history. They’ve won nine championships. They are the Monsters of the Midway, the Super Bowl Shuffle, Sayers, Singletary, Butkus, and Payton.

The Packers have a league-high 13 championships—four Super Bowls, including the first two. They are the only franchise to win three consecutive titles, a feat they’ve accomplished twice. The championship trophy bears Lombardi’s name. They are Starr, Favre, and Rodgers—Hornung, Gregg, White, and Hutson.

Vince Lombardi once said, “We’ve got to win all the games we play, but the one we’ve got to win is the one with the Bears.” With both teams chasing the NFC’s best record, that’s never been truer than it will be on Saturday, when sentiment gives way to modern consequence. This one is not simply about The Rivalry. It could be for all the marbles.

Packers

Implied Team Total: 22.5

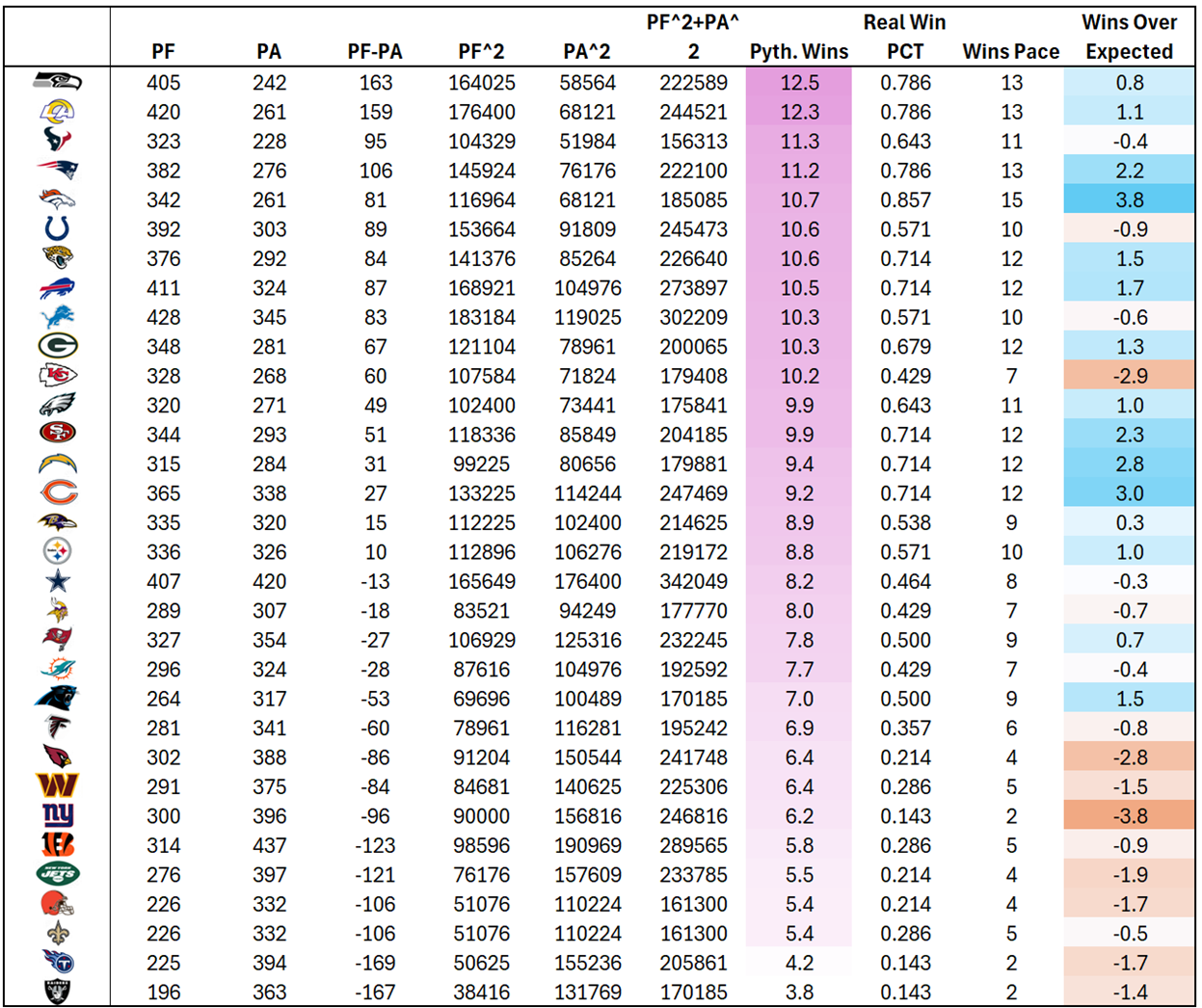

The Bears have the division lead, but according to Pythagorean expected wins, the Packers are the better team. The Bears should be trending for 9.2 wins, while the Packers should be trending for 10.3.

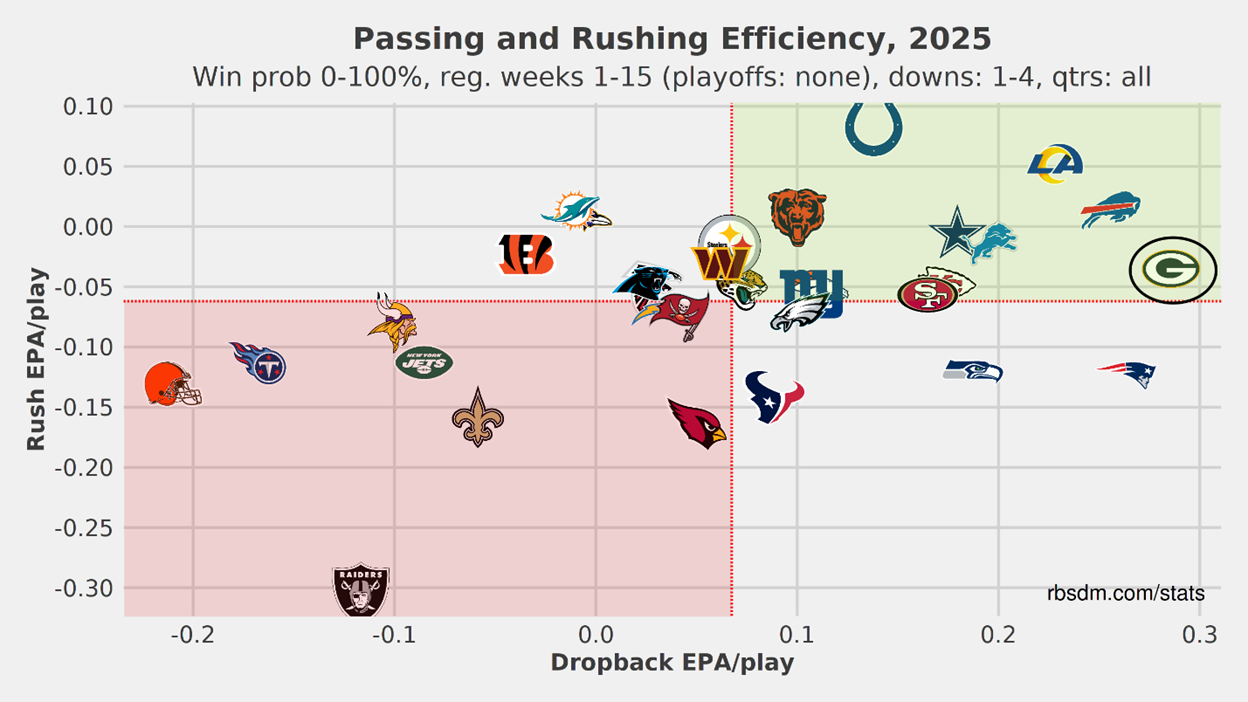

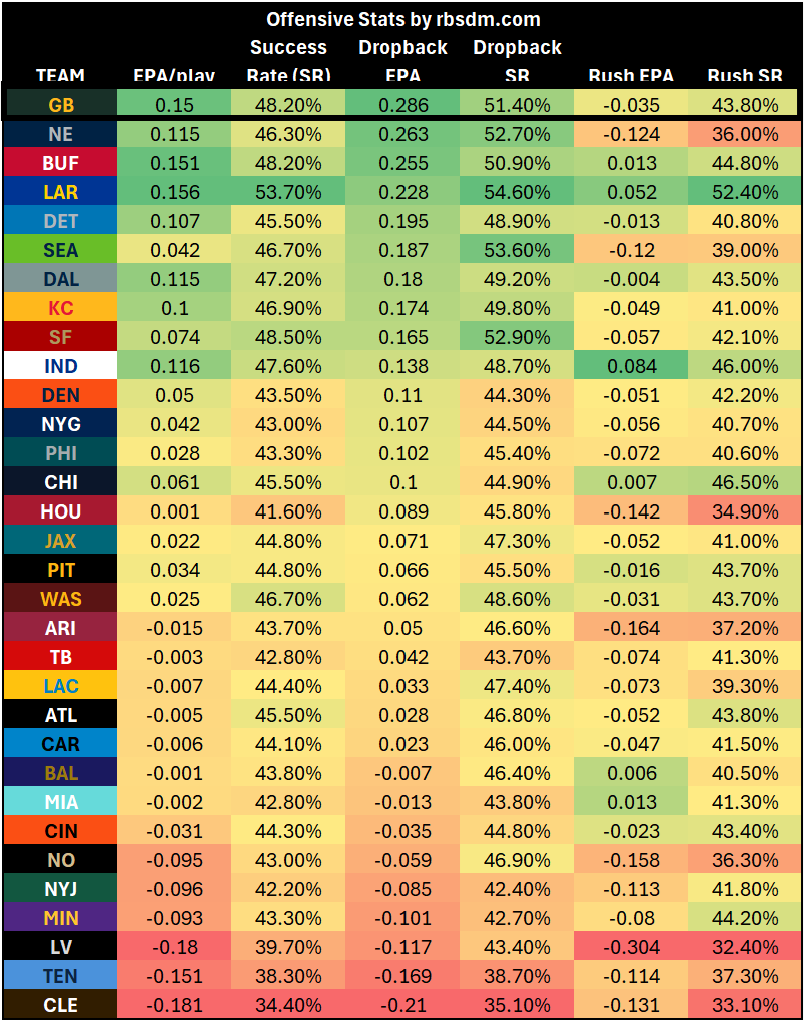

The Packers are about average in defensive EPA allowed, but they are among the best in the league in offensive EPA.

Offensively, they are above average in rush EPA, but they are the best in the league in dropback EPA.

The Packers rank third in offensive EPA per play and fourth in offensive success rate. They rank first in offensive EPA per dropback and fifth in offensive success rate on dropbacks.

The Packers average 27.6 seconds per snap (T-23rd), still around the league’s bottom third, but faster than they historically have been. This has strangely been universal among the Shanahan acolytes this year, as if they had gotten together and held secret meetings in March. Compared to Sean McVay and Kyle Shanahan, HC Matt LaFleur’s pacing has shortened more conservatively.

The Packers’ pass rate is 54% (T-24th). They have spent 660 offensive plays (1st) in a neutral script, so the rate is pretty close to their natural defaults, as they are neither chasing nor killing clock as often as other teams. Their pass rate over expected (PROE) is -0.2% (17th). The Packers average 62 offensive plays per 60 minutes (T-21st).

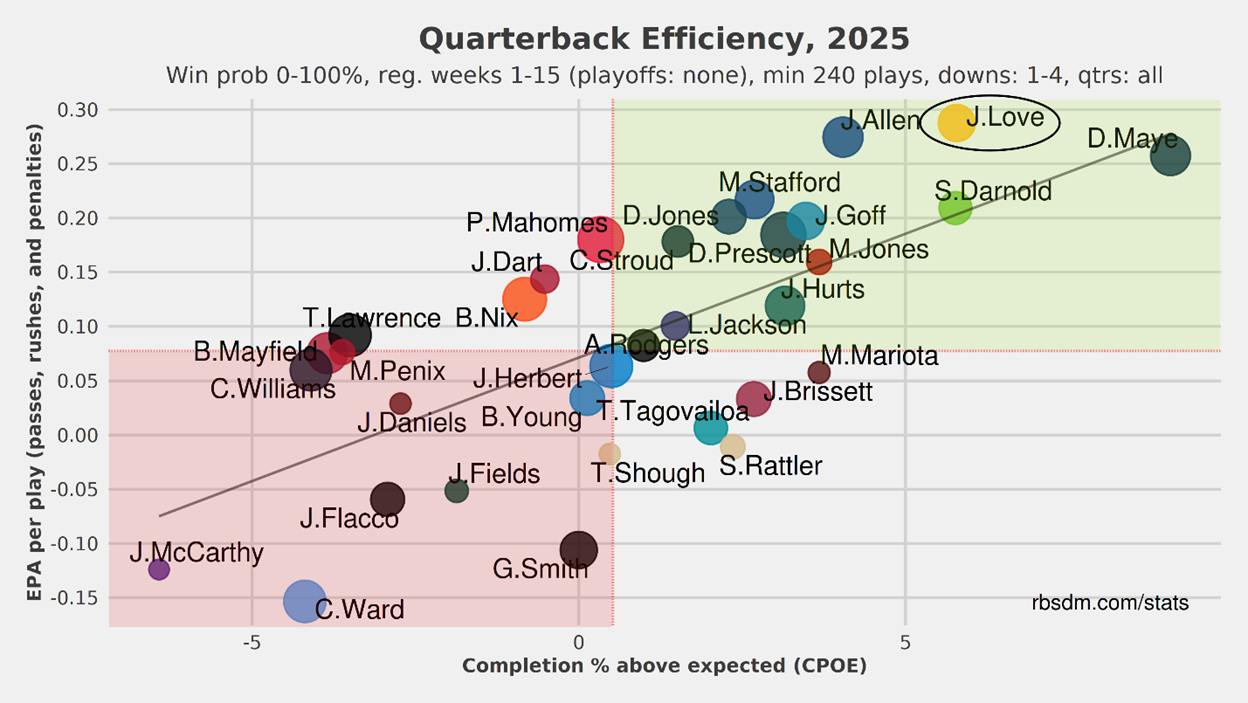

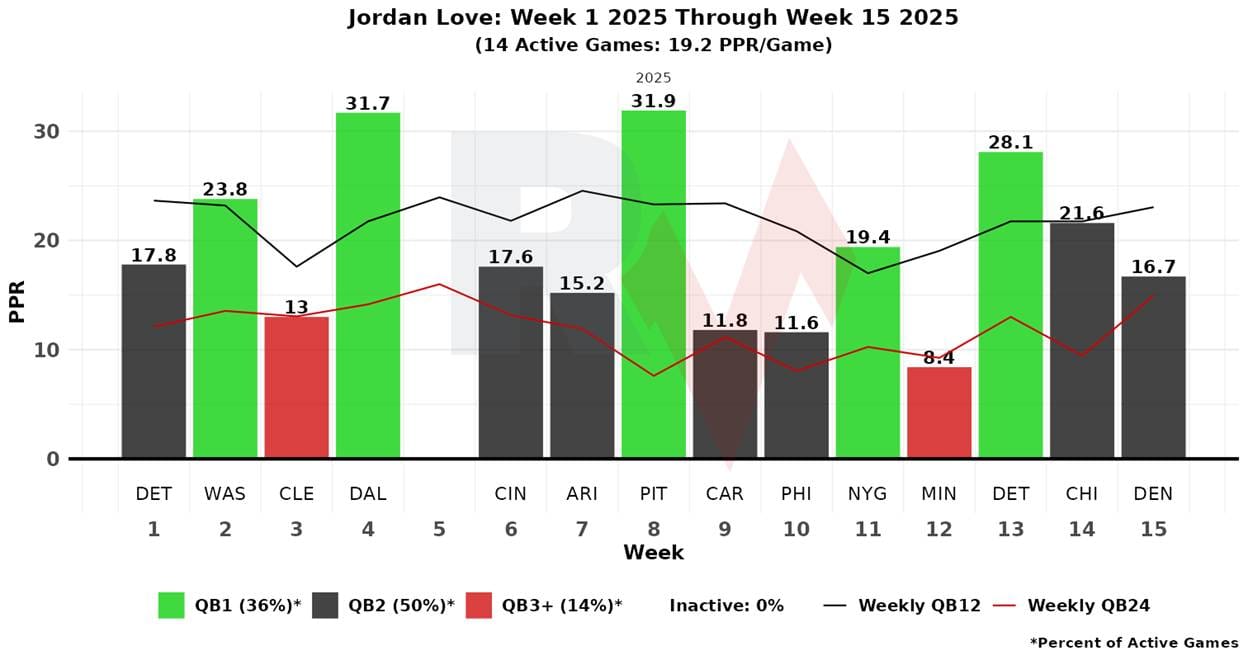

With the Packers' total play volume already low, and dedicating a higher percentage to the run than many teams, we could easily lose sight of how great QB Jordan Love has been in 2025. He ranks second in EPA + CPOE composite, trailing only Drake Maye, revealing a blend of efficiency and consistency.

Being part of a passing attack with middle-of-the-road volume and unprotected by a high rushing platform, Love is vulnerable to lower outputs, but he’s been at least a QB2, or right at the QB2/QB3 edge, all but once. Not only does this mean he’s an unquestioned starter in two-QB and superflex leagues, but he’s usually not blowing up your single-QB lineup either.

On the flip side, Love has been a QB1 five times, including three spike weeks with at or around 30 fantasy points.

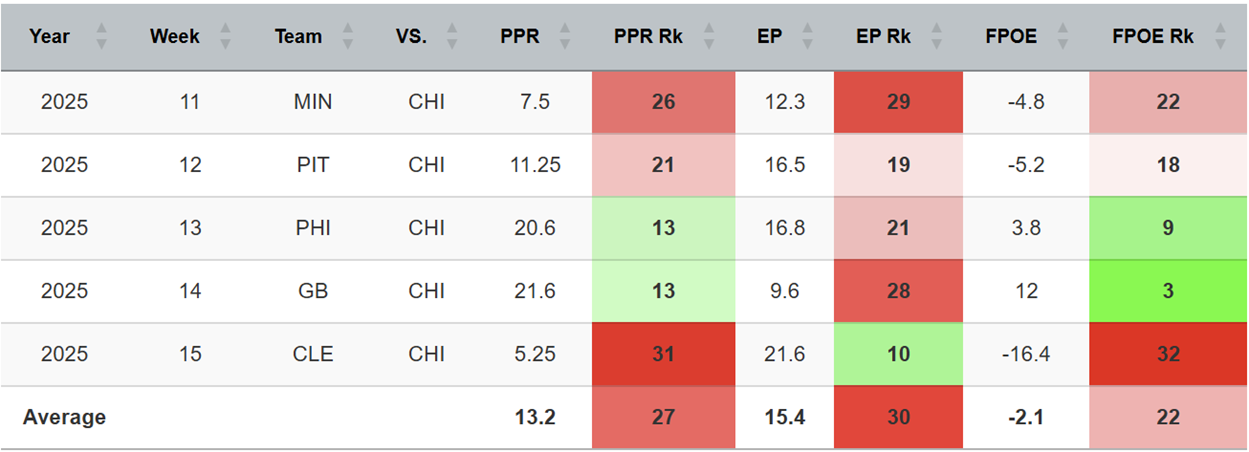

The Bears started the season looking pretty pathetic on defense, but they’ve been far stronger against opposing fantasy QBs of late, holding them to a rank of 27th in their last five games.

The players who cut through? Jalen Hurts and Love himself, who finished with near-QB1 weeks. The players who didn’t? Rookies J.J. McCarthy and Shedeur Sanders, as well as over-the-hill Aaron Rodgers. This probably bodes well for the matchup not being as intimidating as it appears.

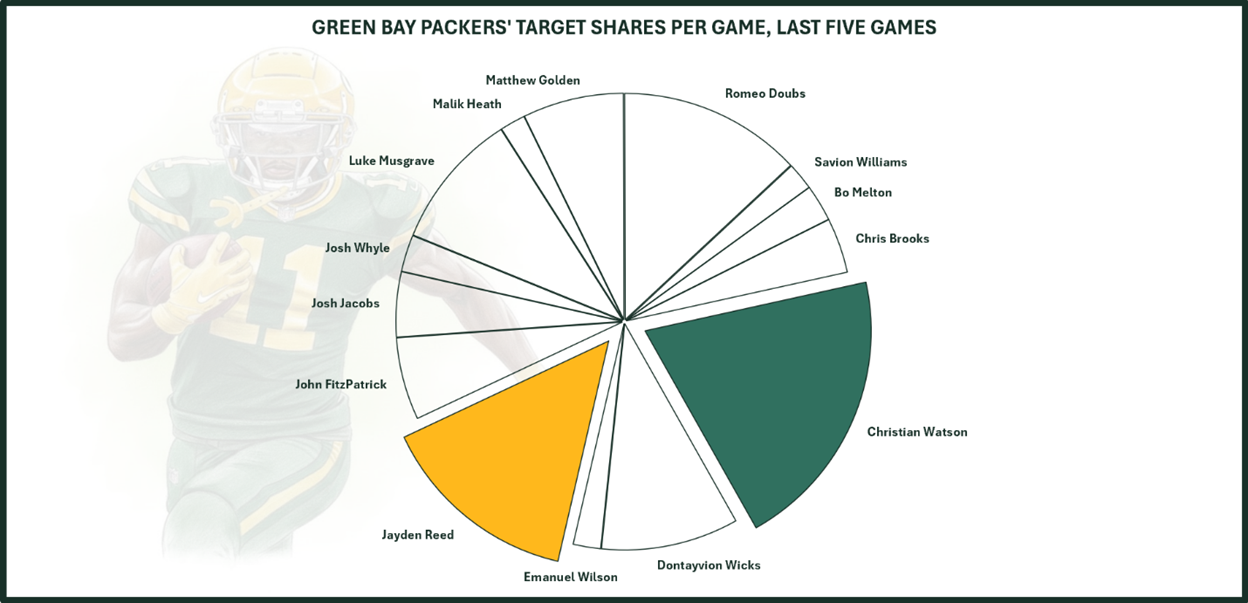

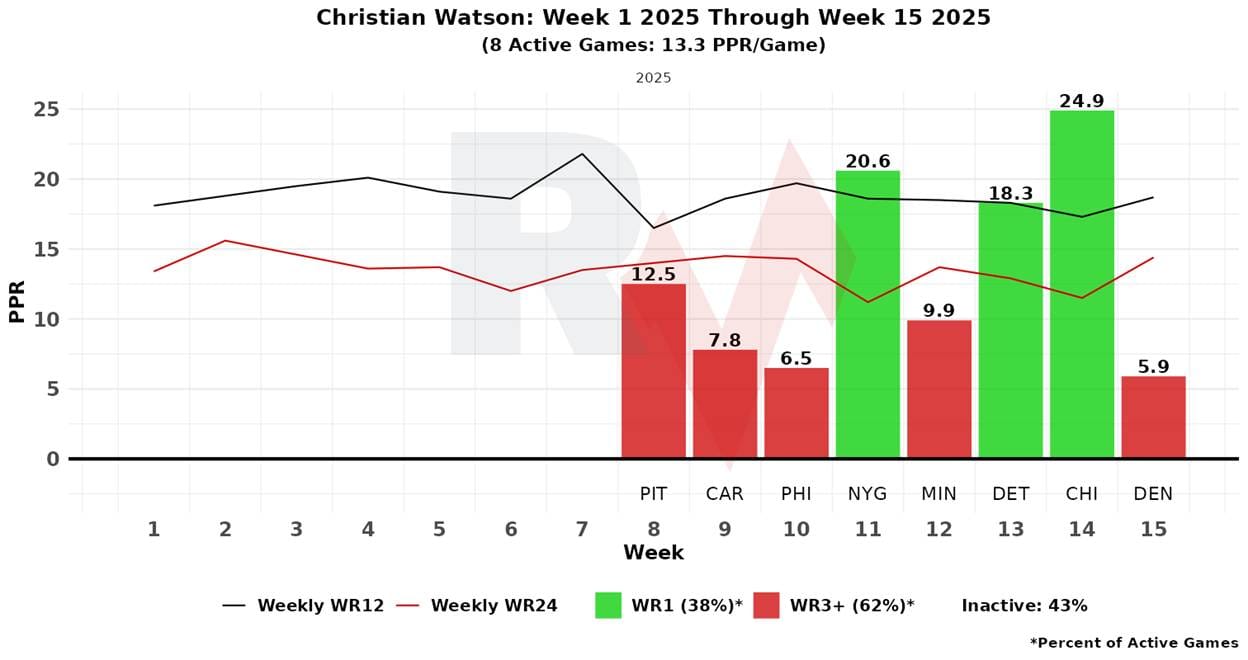

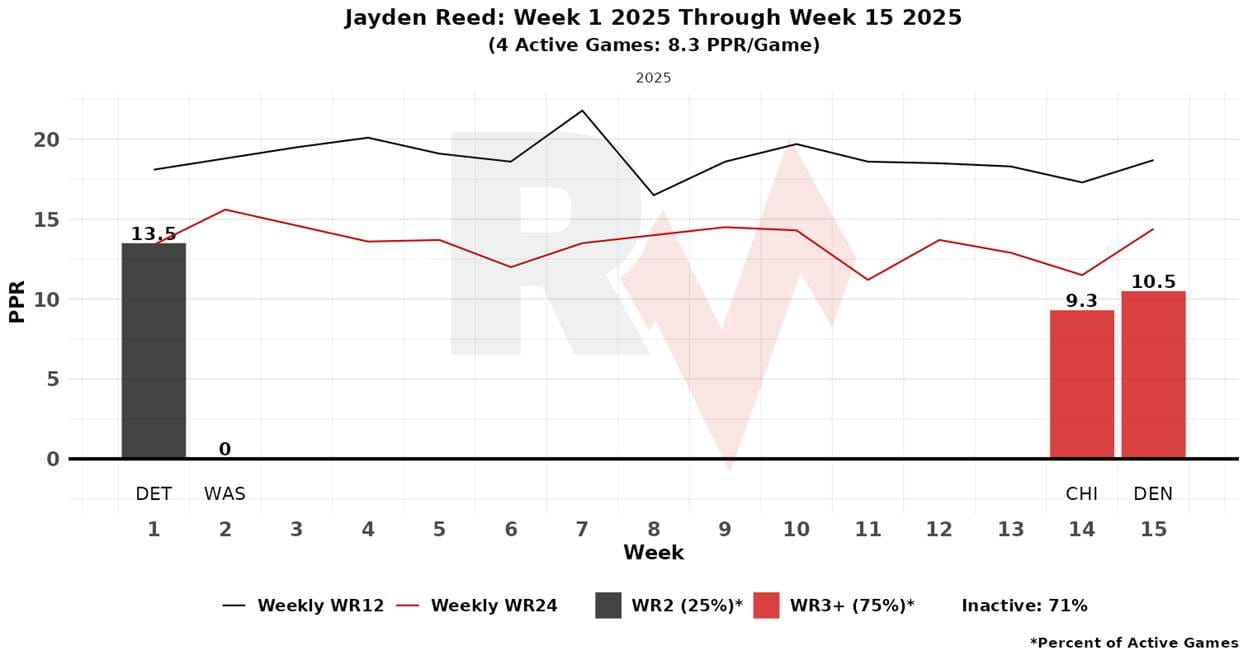

The Packers have had a notoriously broad swathe of pass-catchers involved under LaFleur, at least since the departure of WR Davante Adams. As such, they only have two players with target shares over 15% in their last five games: WRs Christian Watson (21.7%) and Jayden Reed (15.4%). It has been more complicated than we even thought to get a bead on how they prefer to deploy their receivers, however, because there has been a high degree of attrition due to injury.

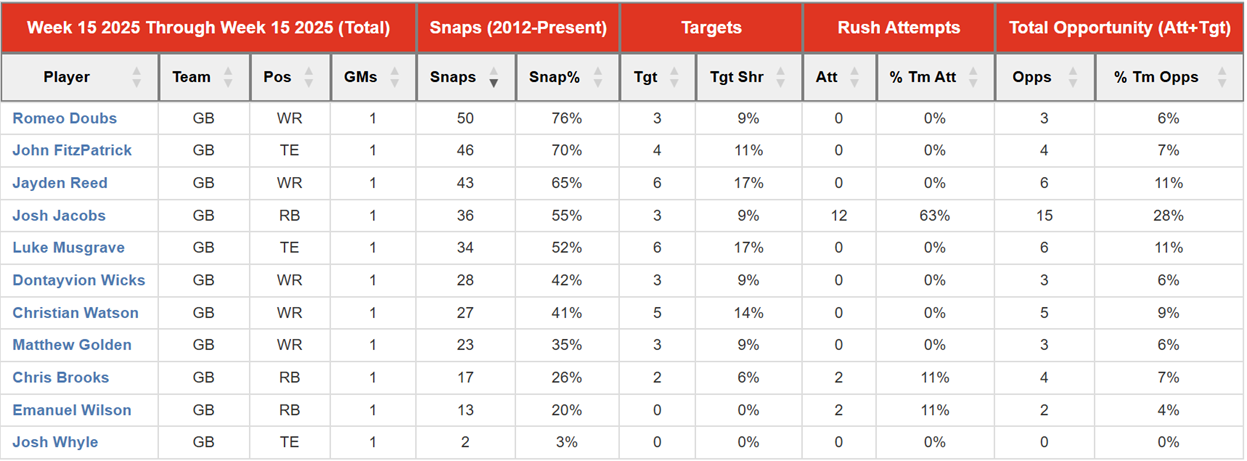

The Packers will be without TE Tucker Kraft all year. Otherwise, they essentially got back to a full-house last week, having WRs Christian Watson, Jayden Reed, Romeo Doubs, Dontayvion Wicks, and Matthew Golden, as well as TE Luke Musgrave, all available. It’s a dreadfully small sample size, but here is how the breakdown of snaps and targets shook out in Week 15:

Watson’s snaps and target shares likely would have been higher if he had not been injured after landing hard on the ground in a tangle with Broncos’ CB Patrick Surtain for the ball. Watson left that game, and it was feared he had a significant injury that would cost him time. Surprisingly, tests came back negative all around, and Watson himself said he “dodged a bullet,” indicating his intention to play Saturday. That said, even if he goes, it’s a white-knuckle ride, knowing it’s a short week and cold outside and knowing that the Packers have a tranche of pass-catchers they can rotate.

When healthy, Watson has clearly been the Packers’ best WR of late, riding a run of three WR1 weeks out of four games heading into last week. However, the question isn’t about him if he’s healthy; the question is if he’ll be deployed as if he is.

Reports leading up to the 8:20 (EST) kick may give us a better indication. However, it might really come down to a fantasy GM’s risk tolerance. Watson’s upside is considerable. Hopefully, for many fantasy GMs with Watson, he is not a dire need, since he was added as a late-season acquisition to an existing stable of WRs.

The best target earner at WR last week was Reed. The thing with Reed is that he’s one of those primary slot players who come off the field whenever the team goes to any formation where there is not a slot WR on the field (like Josh Downs, Demario Douglas, or KaVontae Turpin).

Reed can be extra frustrating, because the Packers under LaFleur will use packages that do not require a slot about 10-15% more than the league average. There are select seemingly opponent-specific game environments that seem to draw them into using more 11-personnel, but it’s hard to predict. Reed’s YPRR from the slot in each of his three seasons has been 2.07, 2.21, and 2.55, so he performs very well given his chances. His involvement, however, is a crapshoot.

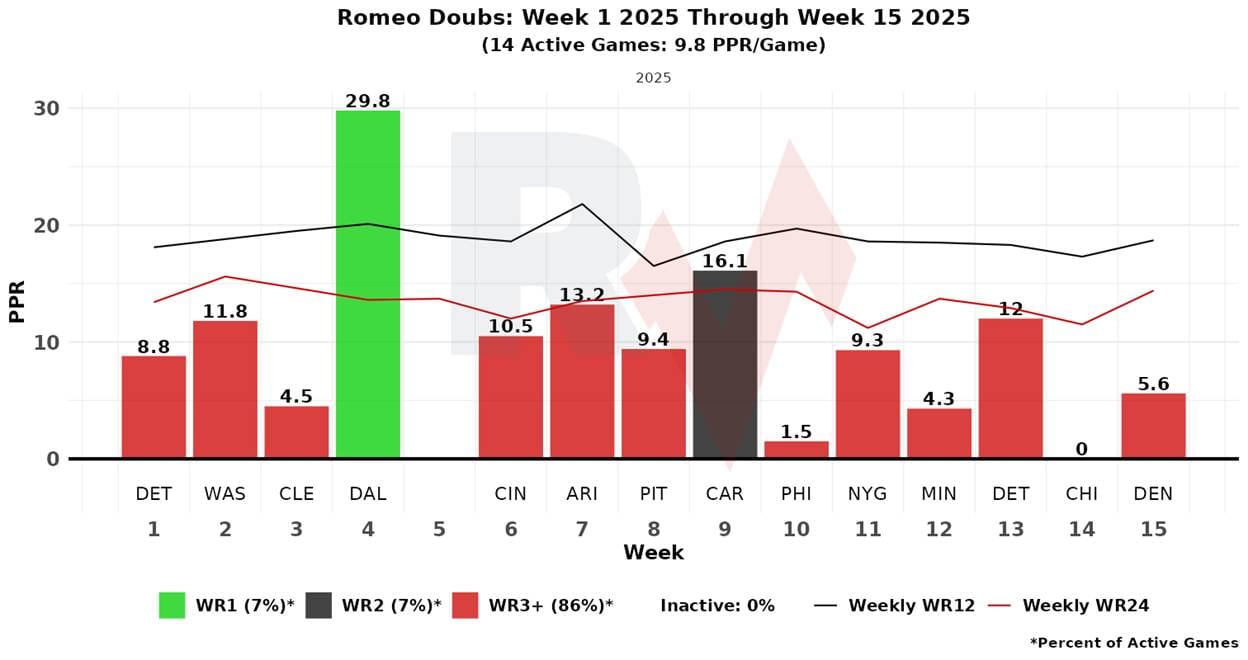

WR Romeo Doubs runs the most routes as a Z-receiver who doesn’t come out on any personnel package. He isn’t overly efficient. He is capable of putting up meager but usable lines; his one spike week came in a shootout with Dallas with a combined 80 points. He’s not a high upside option, but he could be usable, especially if he can score a TD.

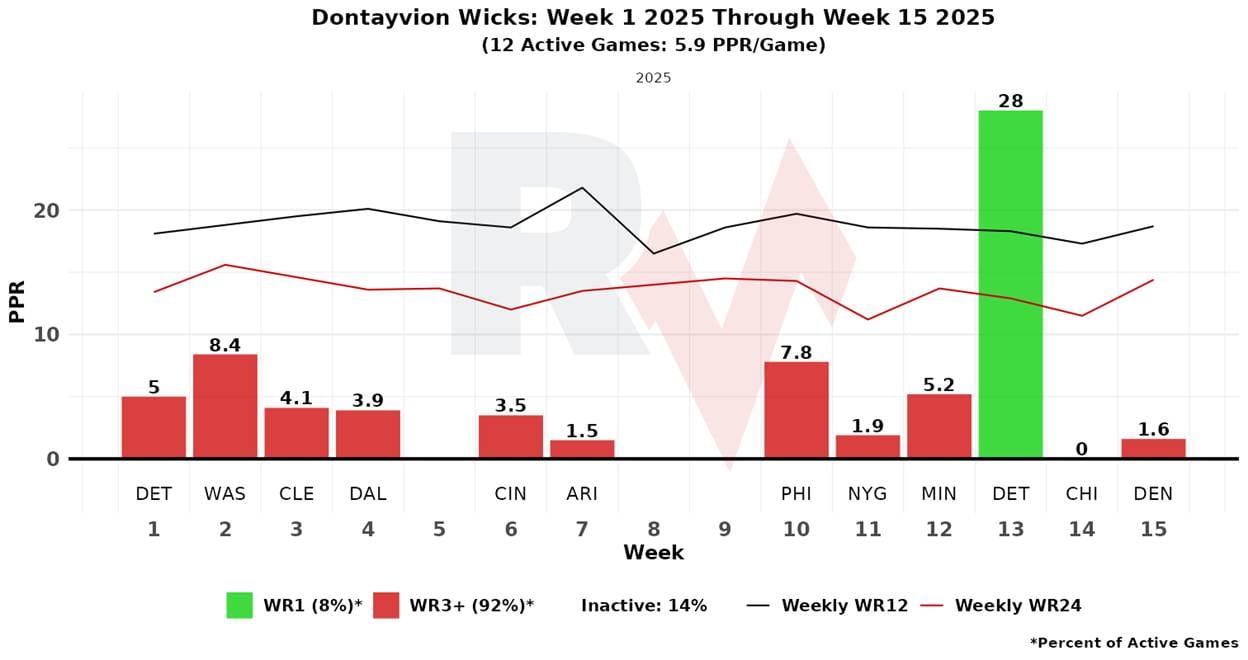

If Watson can’t go, tradition has it that WR Dontayvion Wicks will fill the majority of his snaps. Wicks has had single-digit PPR performance in every game but one, which was a blow-up game in Week 13 in another shootout where Wicks caught two TDs. In that game, with no Reed, Wicks and Watson were splitting time in the slot—each running nearly 40% of their routes from there. This would likely not be the role Wicks would occupy if Watson is out; he would be used far more often out wide. This all comes with a caveat: technically, Wicks is questionable, though he is expected to play.

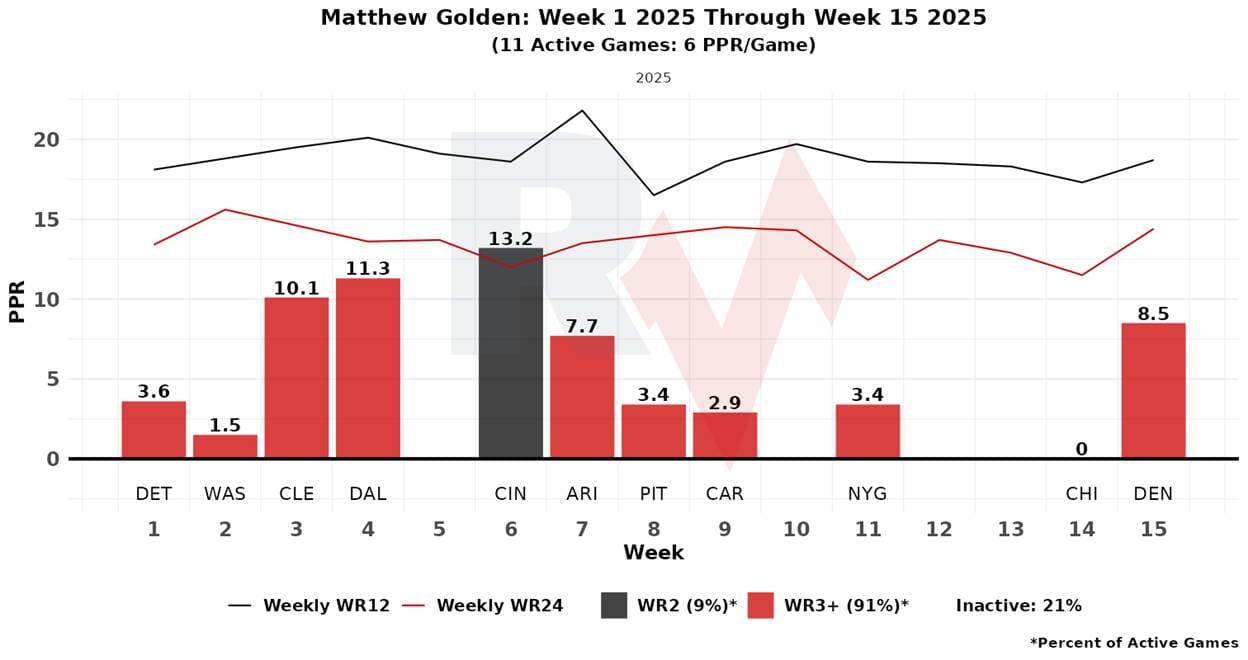

The wild-card is WR Matthew Golden, a first-round rookie. Golden has actually been more consistent than Wicks. He runs out wide more than from the slot. He is not a traditional field-stretcher—Watson is far more like that than anyone else. Watson’s aDOT is 19.3 while Golden’s is 13.8. It isn’t that Golden is being boxed out entirely; he’s third on the team in routes. He just hasn’t really put it all together yet. Resistance to using him is founded; if Watson and Wicks are both out, however, Golden should be considered a strong play.

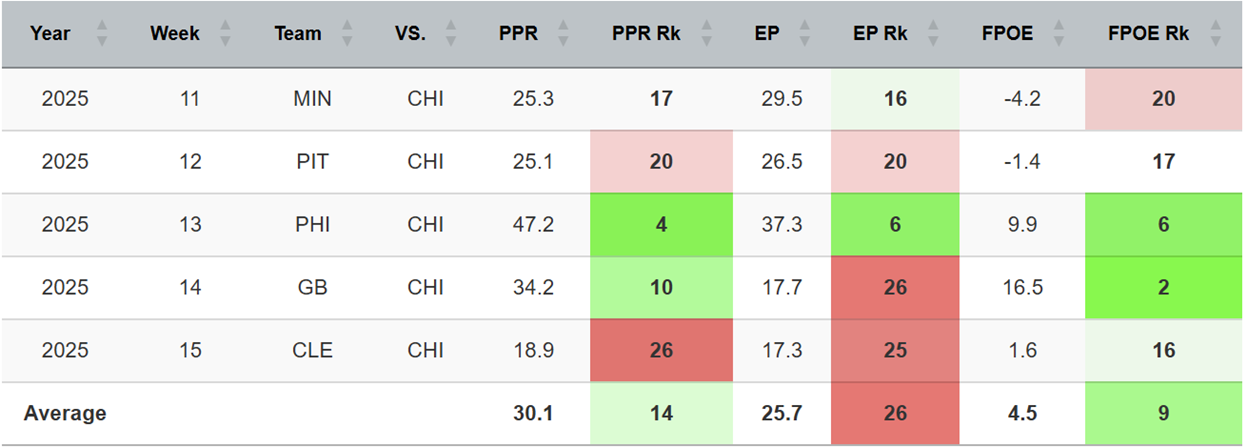

The Bears have surrendered the 14th-most fantasy points to opposing WRs in their last five games. There is a disparity between the ranks of the expected points (EP) allowed and the FPOE. Oddly, this imbalance is almost entirely driven by the Packers’ WRs, who were highly efficient against Chicago in their last meeting.

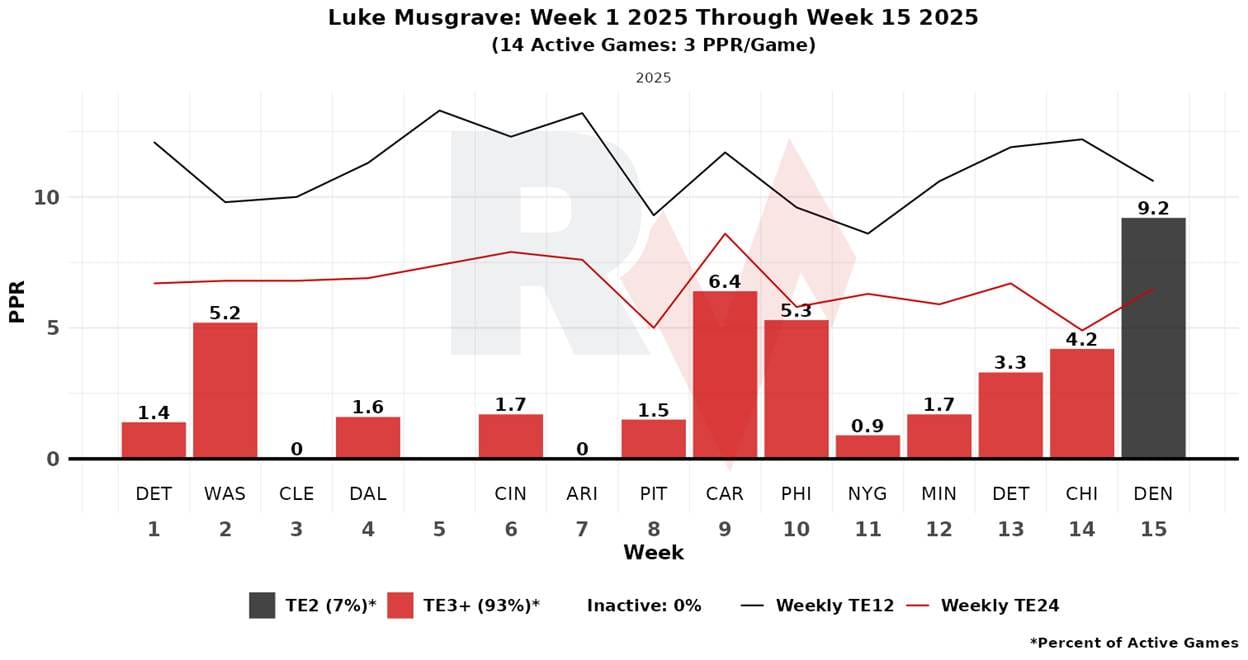

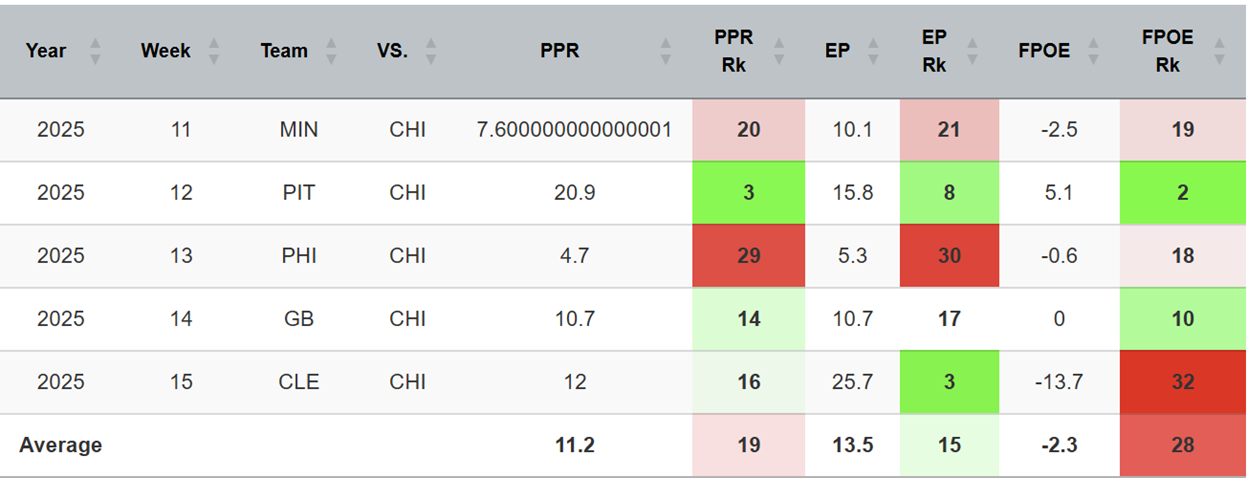

Kraft was a bit of a revelation this year, and his play style is distinct from Musgrave’s. He didn’t draw much volume, but his efficiency, particularly after the catch, was off the charts. Strip that away, and Musgrave is left with the less lucrative role, without a realistic path to replicating the efficiency that drove Kraft’s fantasy production.

Chicago has been a middling matchup for opposing fantasy TEs in their last five games. Notably, the bigger the name, the better they’ve seemingly done.

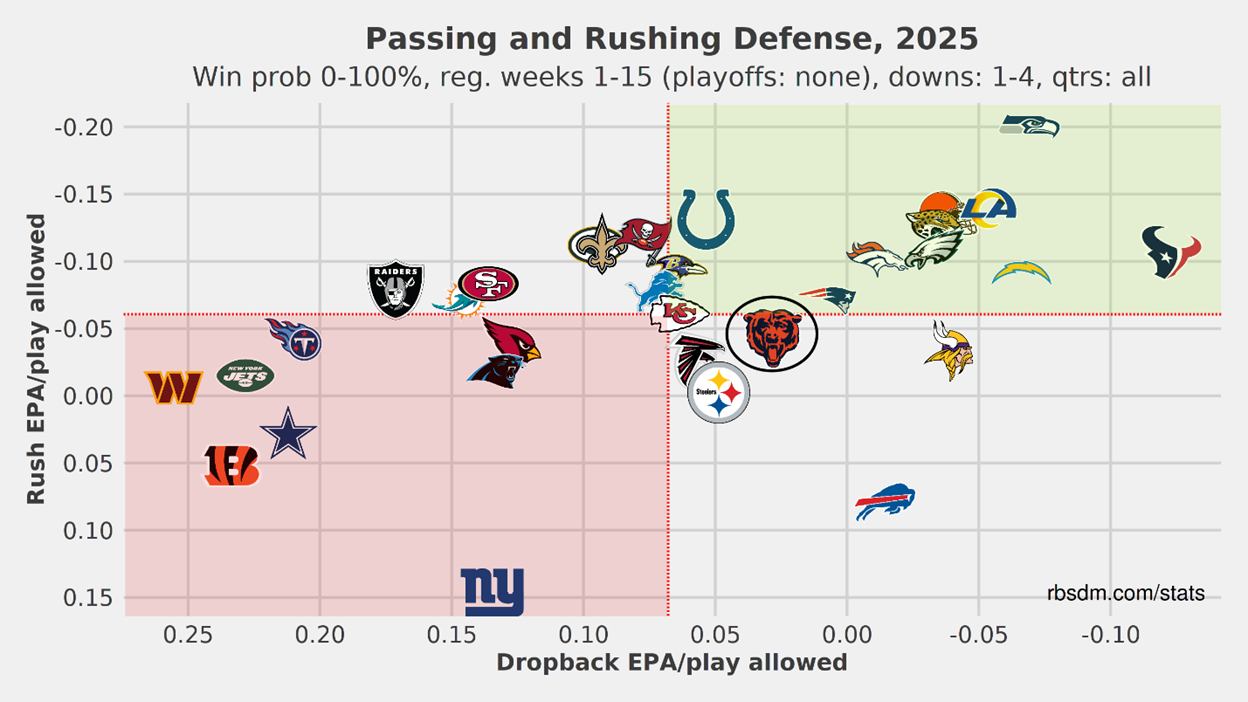

Chicago’s defense is above average in dropback EPA allowed, but below average in rush EPA allowed.

The Bears rank 13th in EPA per play allowed and 23rd in defensive success rate.

They rank 12th in EPA per dropback allowed and 16th in defensive success rate on dropbacks.

Chicago uses man defense at a rate of 30.1% (8th) and two-high safeties at a rate of 51.6% (12th). Their most common alignments are Cover 3 (28.7%) and Cover 2 (22.7%). They blitz at a rate of 27.2% (10th).

Fantasy Points’ coverage matchup tool assigns a zero-based matchup grade to each pass-catcher based on their opponent’s use of specific types and rates of coverage and how that pass-catcher performs against them. Positive numbers indicate a favorable matchup and negative numbers indicate an unfavorable one.

Based on the model, Watson doesn’t have a great matchup (-12.9%), likely due to the amount of shell coverage Chicago runs. Golden (+10.5%), Wicks (+3.1%), and Doubs (+1.2%) all show up with favorable matchups. Reed hasn’t played enough to qualify for the tool’s minimums.

PFF’s matchup tool is player-based, pitting the PFF ratings of individual players against each other for an expected number of plays based on historical tendencies and rating on a scale from great to poor.

Based on this, Watson and Reed’s matchups grade out as great; Doubs’ grades out as good; Musgraves’ grades out as fair.

The Packers’ offense has allowed a pressure rate over expected (PrROE) of 9.20%, while the Bears have generated a defensive PrROE of 0.59% (30th). The Packers may be without RT Zach Tom, their best offensive lineman, and on the wrong side of questionable, but it is not clear that the Bears could capitalize, regardless of who the Packers put out there. The matchup is fairly neutral on paper—bad against bad.

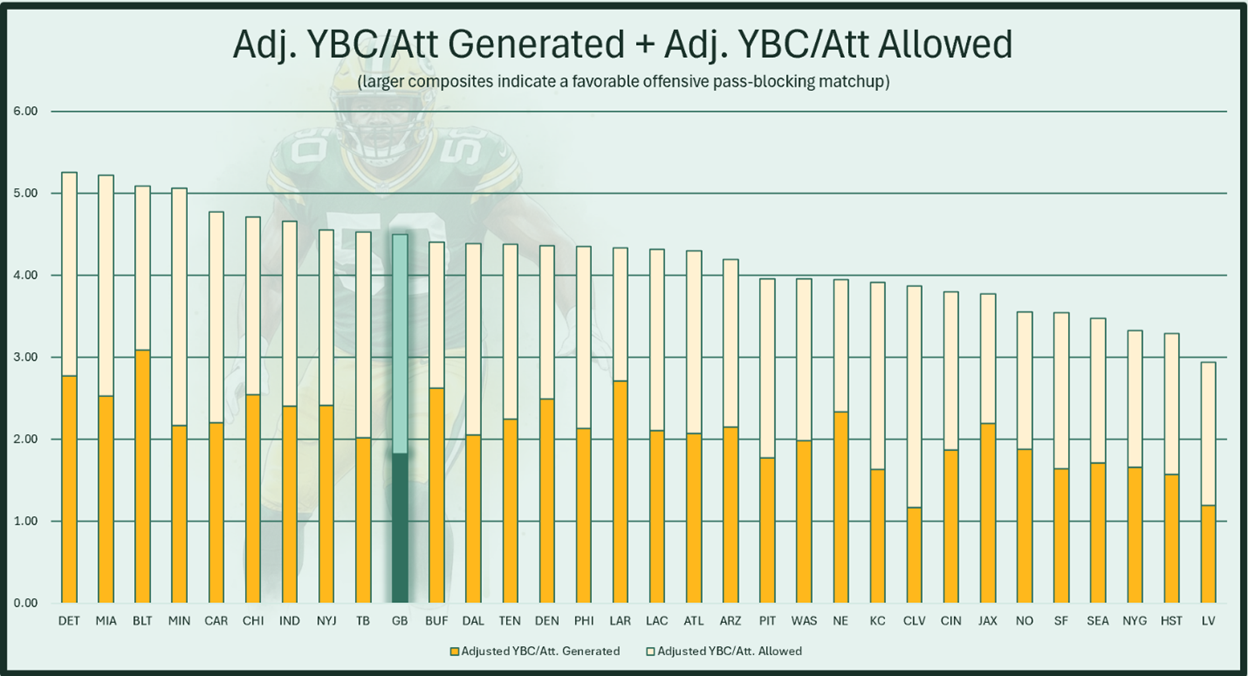

The Packers only generate 1.83 adjusted yards before contact per attempt (adj. YBC/Att, 25th). The Bears allow 2.67 adj. YBC/Att defensively (29th). This is the same story—bad on bad, but on these margins, the Packers appear to have a slight advantage in run blocking. Again, though, they may be without Tom, which could be more significant to the run-blocking matchup.

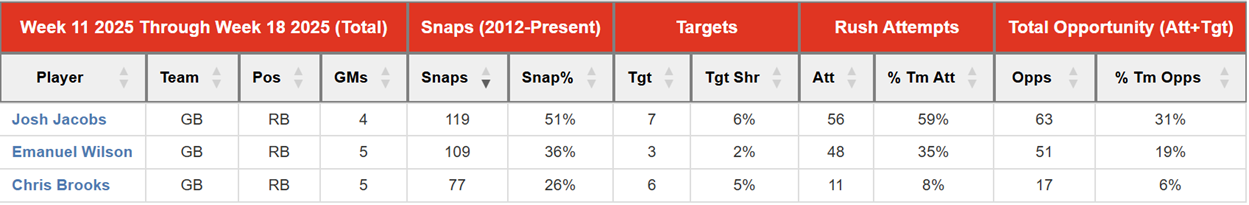

The Packers rank 12th in offensive EPA per rush and sixth in offensive success rate on rushes. The Packers have operated as a bit of a bell-cow situation under LaFleur since last year, when Jacobs arrived. Jacobs has been fighting through a ton of ailments: a quad strain early in the year, a stinger, an illness, and now a knee and ankle injury. Jacobs is listed as questionable, but is expected to miss the game. If so, Emanuel Wilson should fill in.

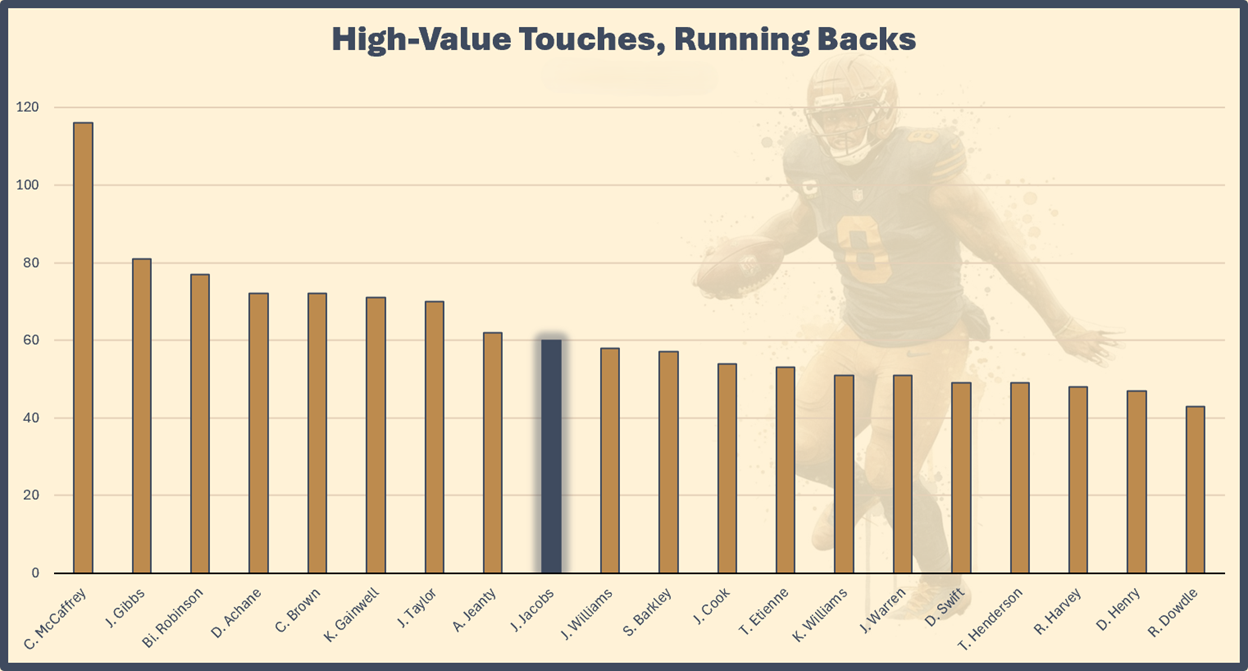

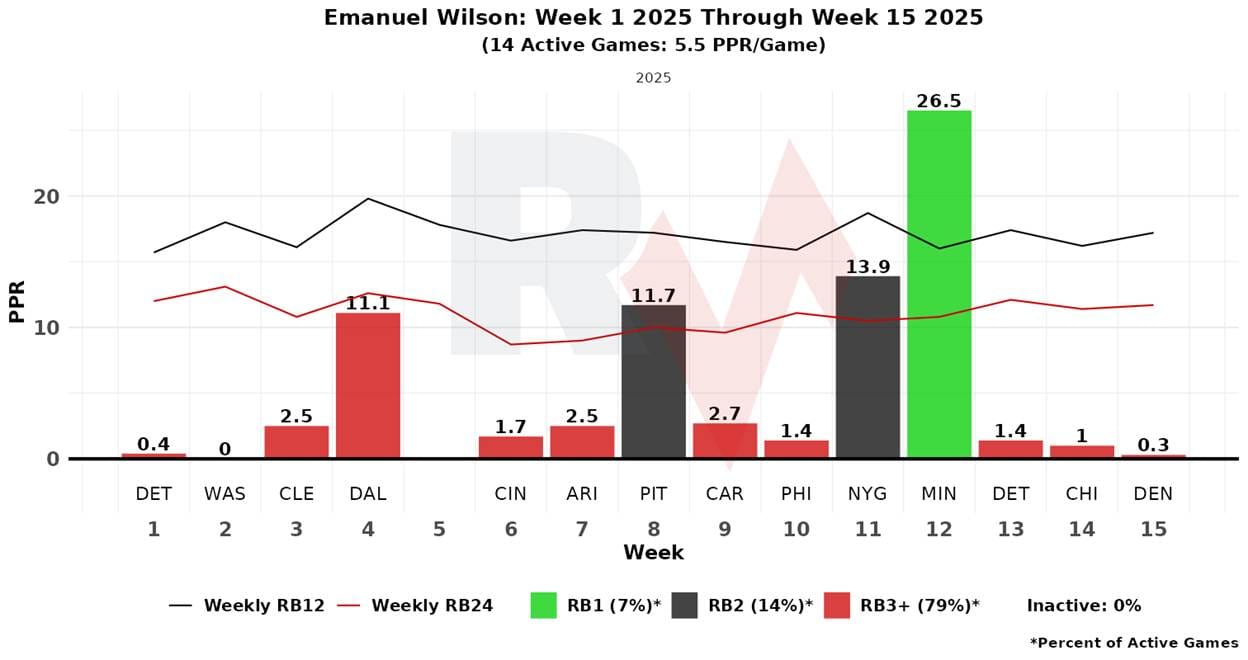

Jacobs is ninth in high-value touches (HVTs, 60). In the Week 12 game against Minnesota (a tough defense, by the way), Wilson had five of his own.

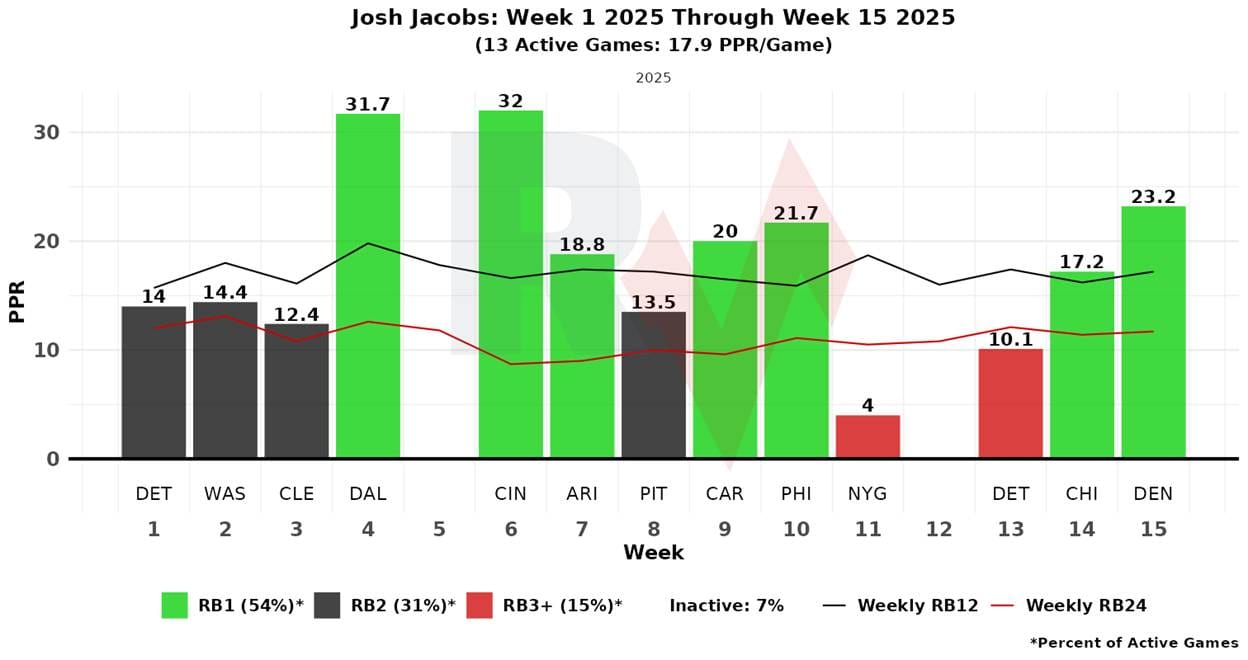

Jacobs has been an RB1 in seven of his 13 games. His only single-digit output came in Week 11, a game he left early with an injury.

Wilson outperformed Jacobs in Week 11, then got the bulk of the work in Week 12, putting up a two-TD effort that would have ranked as Jacobs’ third-best game of the year.

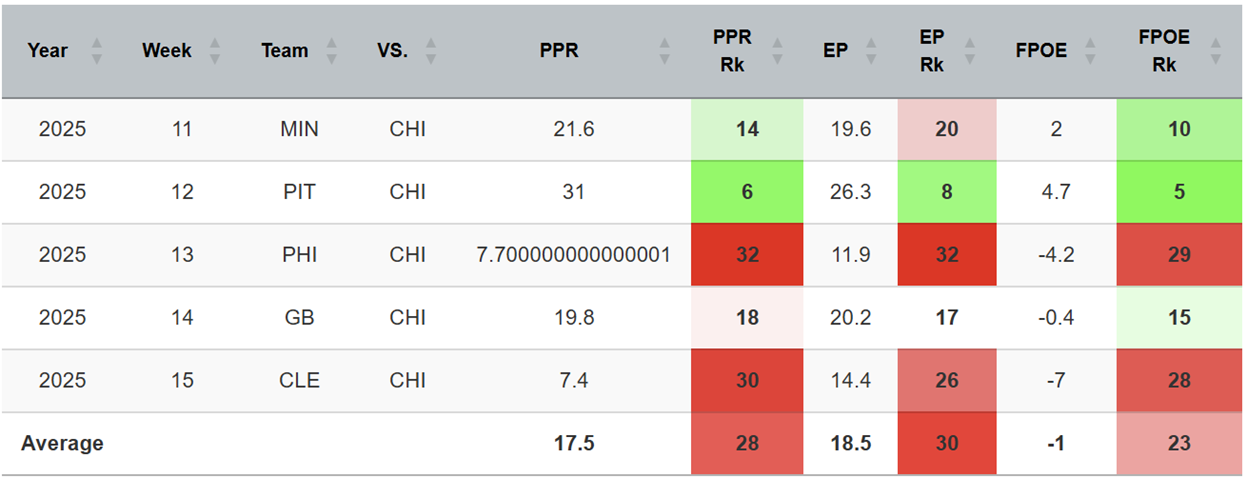

The Bears rank 20th in EPA per rush allowed and 26th in defensive success rate on rushes. In their last five games, they’ve only allowed their opponents to rank 28th in PPR points. This is a sample that includes Saquon Barkley and Jacobs himself.

Wilson will likely get a heavy workload again, but we shouldn’t expect the same results we got in Week 12. He’s more of an RB2.