Quick Slant: SNF - The Two Texans-es

Mat Irby’s Quick Slant

The palms and sunshine of Miami stood in stark contrast to the cool midwinter of Dallas, where Hunt, 26, worked at his father’s oil company. He was from money; he had been trying relentlessly to acquire a piece of the NFL—recommending expansion, offering to buy—but nothing had panned out, and his desperation only grew. So Wolfner’s call to meet about buying opportunities, especially after all the failed attempts with him, had Hunt’s pulse buzzing like a crankshaft. He knew he was down to the felt, and this was his last chip to play.

The Fontainebleau, the quintessential icon of Miami MiMo luxury in the late ’50s, curved around its covered vestibule like a pastel hug at the edge of Mid-Beach. The taxi dropped Hunt into a swarm unlike the measured insularity of Highland Park. Jet-setters in Cary Grant suits and fedoras, society ladies named Bunny and Bitsy in Chanel, international tycoons, A-listers, dignitaries, even royals—everyone buzzed like cogs in a Swiss watch. Hunt closed his eyes and tossed up a silent prayer before entering.

Inside the Bleau Bar, Hunt nursed a club soda while Wolfner sipped an old-fashioned. He tried to square what he’d just heard before he interrupted the lawyer, who droned on about it. Hunt’s heartbeat thudded like a jackhammer, his breath jammed like it was caught in a clogged filter. The steak in front of him was cold, barely touched. As he removed his browlines and wiped his forehead, his gaze stayed perpetually forward, as unfocused and chaotic as a particle in Brownian Motion. Finally, he met the moment with the urgency he felt.

“But, but, but, wait—” he said, grabbing the swirling room by the handrail and making it stop.

“Mr. Wolfner, I’m sorry. You’re saying you only want to sell me a minority share? But you would keep the team . . . in Chicago?”

He was young, but savvy enough to understand precisely what was being offered. He’d be on the board, but his inputs would amount to suggestions. He’d hobnob with Chicago elites (which didn’t interest him in the least, having grown up among barons back in Dallas and finding them all so banal). He’d get a Chicago Cardinals windbreaker, of course—maybe a pair of cufflinks. And all it would cost was an upfront fee and a share of the team’s annual net losses. For that, he’d be part of the game, but he wouldn’t get to play it.

Wolfner’s confirmation, insolent and haughty, faded into the chatter of nearby patrons as he burbled on about how the deal would benefit both parties. Pressure built inside Hunt until he couldn’t take the ringing in his ears.

“I’m sorry,” Hunt ticked, tossing cash on the table and fleeing like a wounded deer.

Hyperventilating, shaking, soaked in all this stupid humidity, he wandered outside, bursting past the beehive of activity, across Collins Avenue, and straight to the sand, which quickly filled his wing-tips. Stopping to feel the breeze, he found calm. Looking out, he fixated on the gentle, cerulean waves. Clarity smacked him in the lips like a binky, and he stood still for an eternity. Then, when he was ready, he spoke quietly to his own thoughts.

“Yeah,” he whispered aloud, eyes fixed on a scene from his imagination, a smile forming, “Why not?”

If the NFL wouldn’t let Lamar Hunt have a team, by God, he would start his own league.

From this last futile swipe, glancing errantly off “The Shield,” the AFL was born, the Dallas Texans were born, and in a roundabout way, the Cowboys were, too, as new commissioner Pete Rozelle chose a rushed expansion to Dallas rather than letting an alternate team plant its flag there alone.

It didn’t take long for Hunt’s Texans to feel the squeeze of a market that quickly became smitten with Landry and the star, prompting him to cut his losses and head to Missouri; and since Kansas City Texans made no sense, Chiefs it was.

Hunt’s Chiefs became emblematic of the NFL’s manifest destiny—the team that set crucial dominoes in motion. A few short years later, they played in the first AFL-NFL Title Game—now known as Super Bowl I (a phrase coined by Hunt)—instantly weaving themselves into the story of the post-merger NFL.

The old name was resurrected in 2002 and applied to the Houston Texans, who also serve as a pivotal marker in the league’s expansion process; they are the 32nd and, for now, final NFL team. In a way, it all comes full circle: Hunt’s decision to choose revolution created a Texans team that pushed the NFL to its highest heights, eventually culminating in a Texans team that rounded it out. And tonight, they fight each other for their playoff lives—a cornerstone defense vs. an electric offense, and a loss that must be given, one that may well topple the season of a team that deserves January.

Texans

Implied Team Total: 19

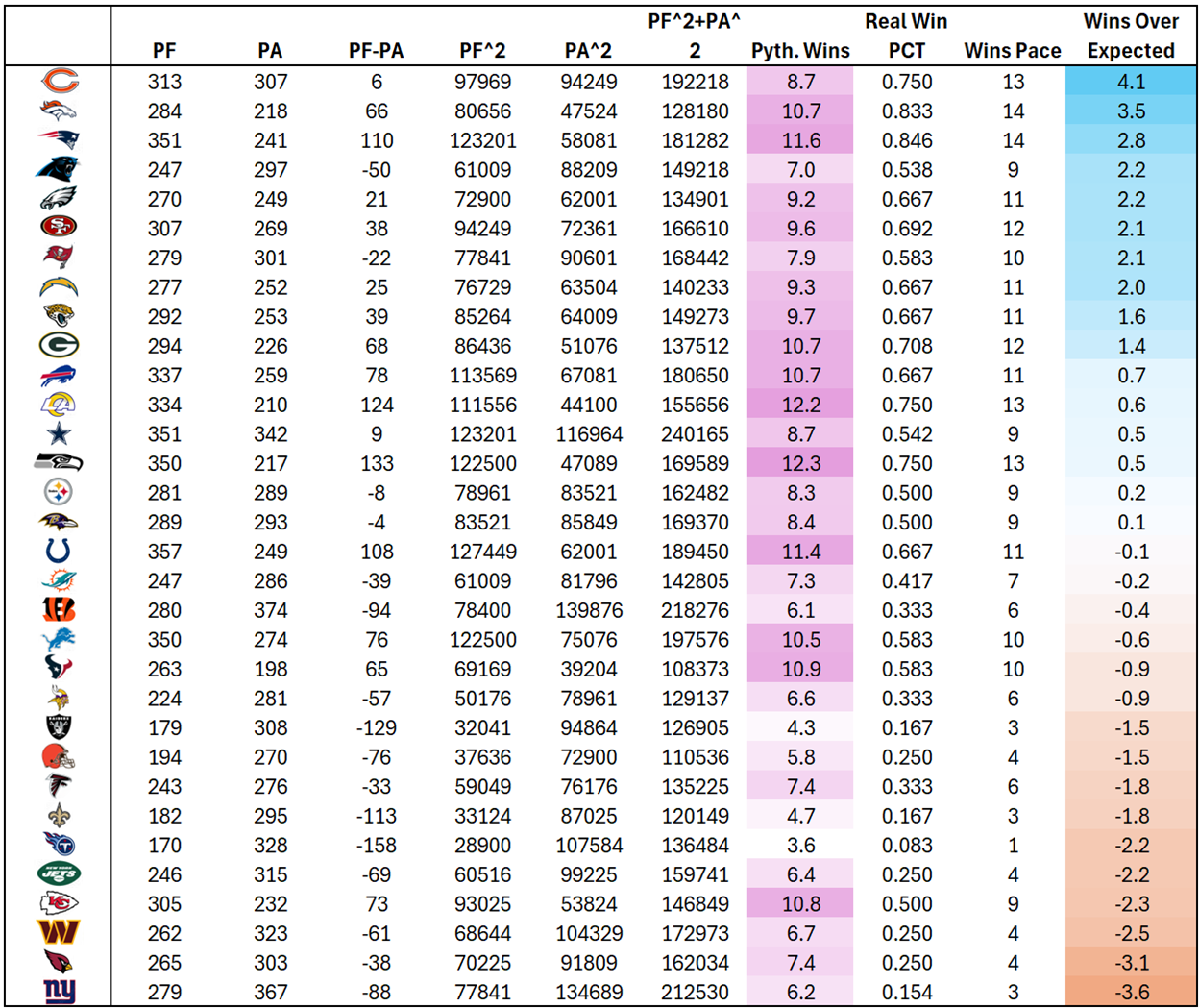

The Texans have been on a heater, winning four in a row. They, like Kansas City, are below expectations; based on Pythagorean wins, each would be expected to pace at almost 11 wins, but is instead in imminent danger of missing the playoffs entirely.

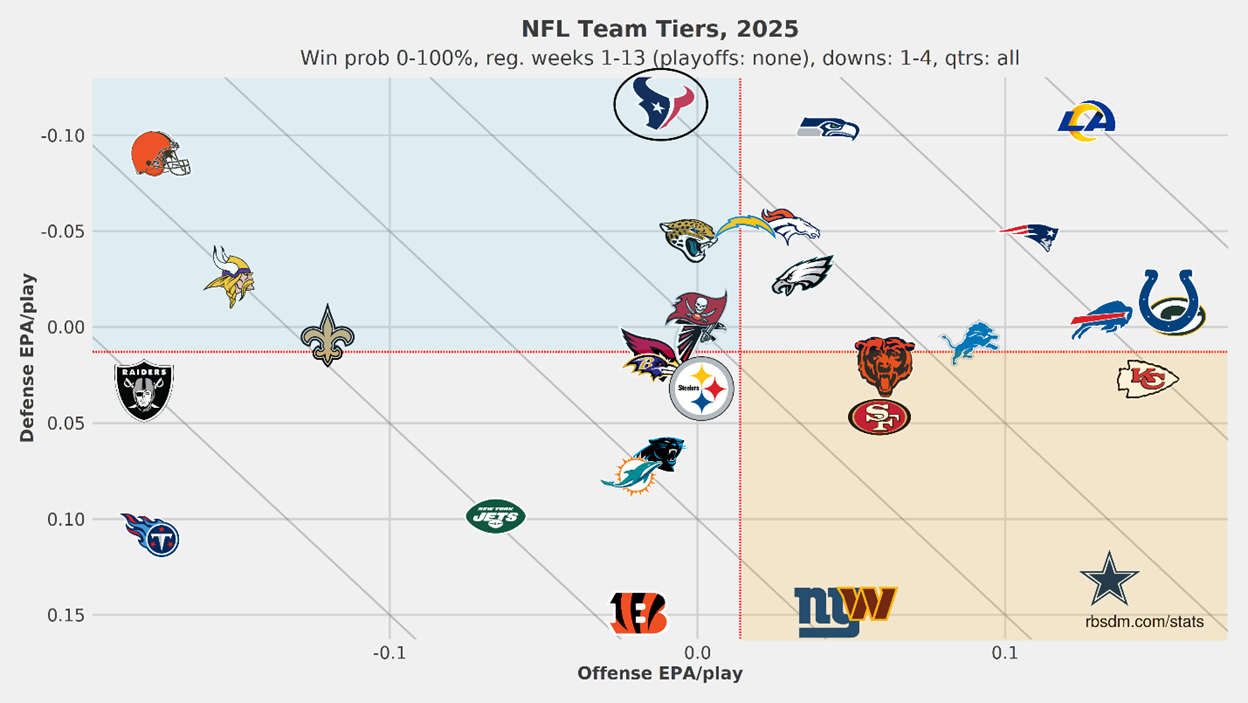

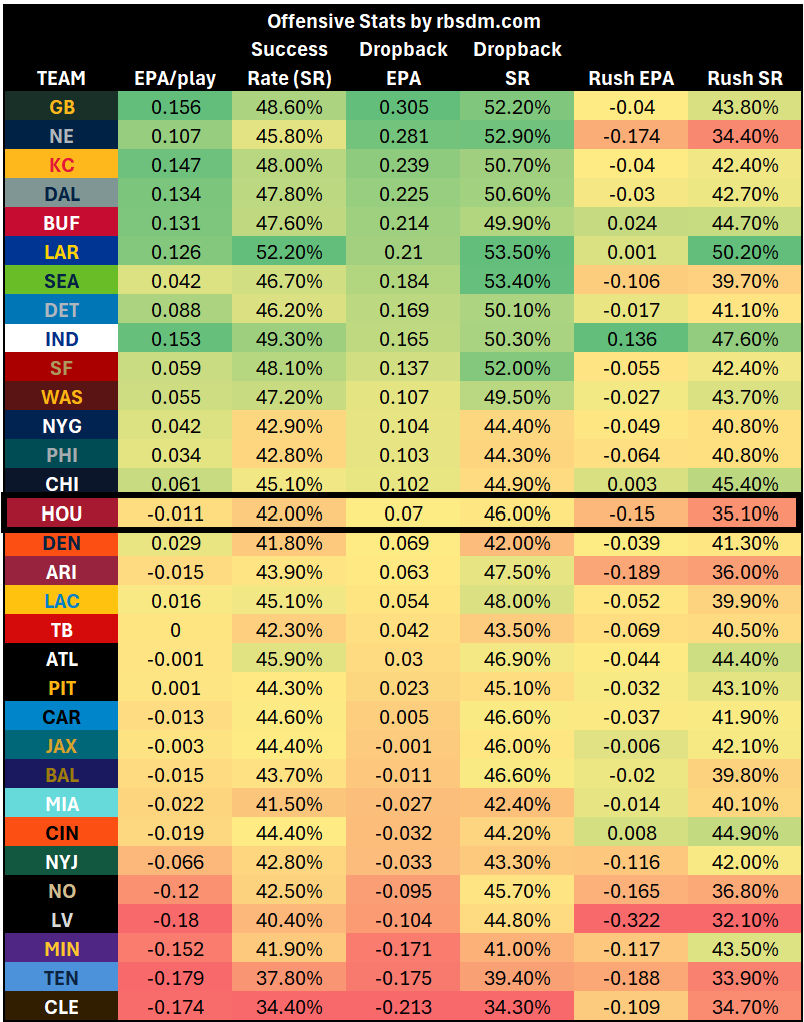

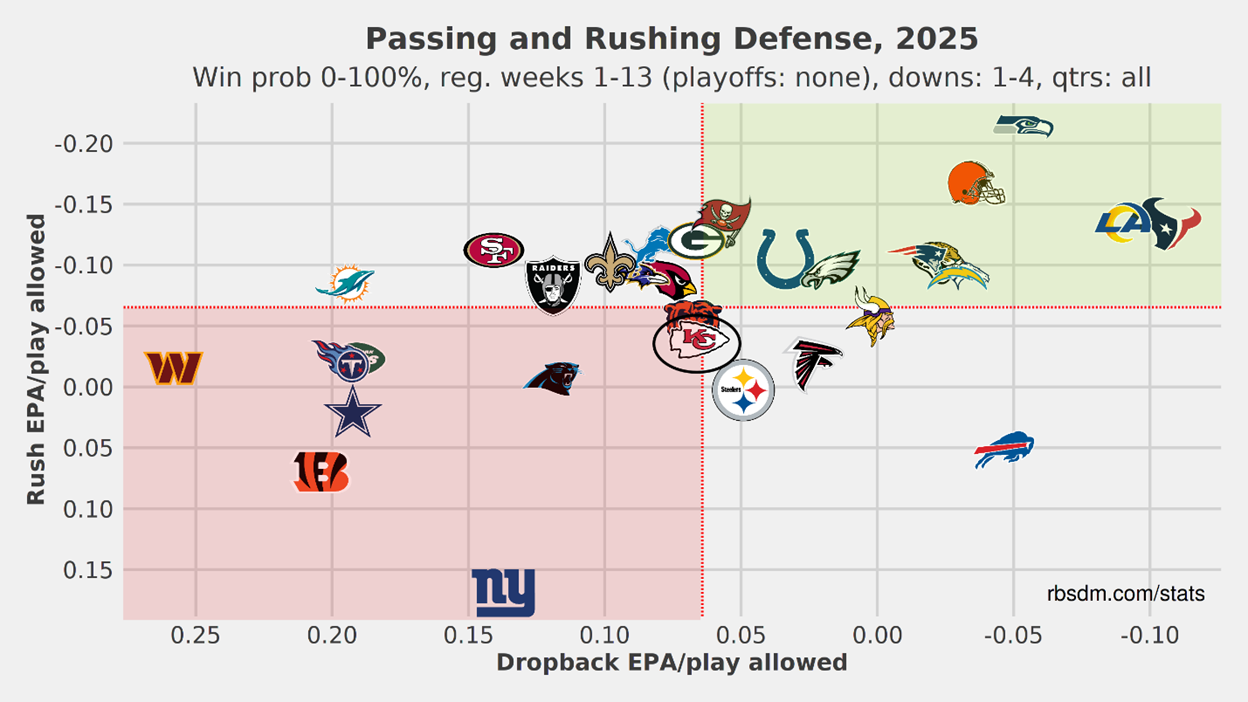

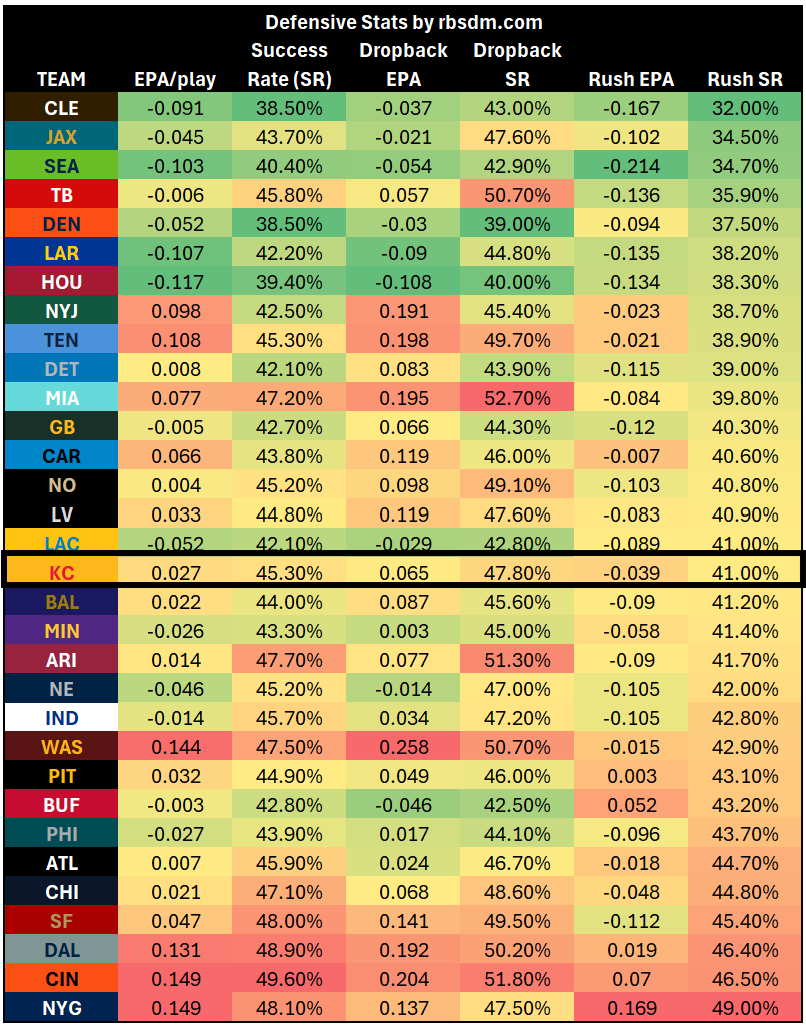

The Texans are most likely the best defense in the NFL; they have the lowest EPA per play allowed. They are slightly below average in offensive EPA per play.

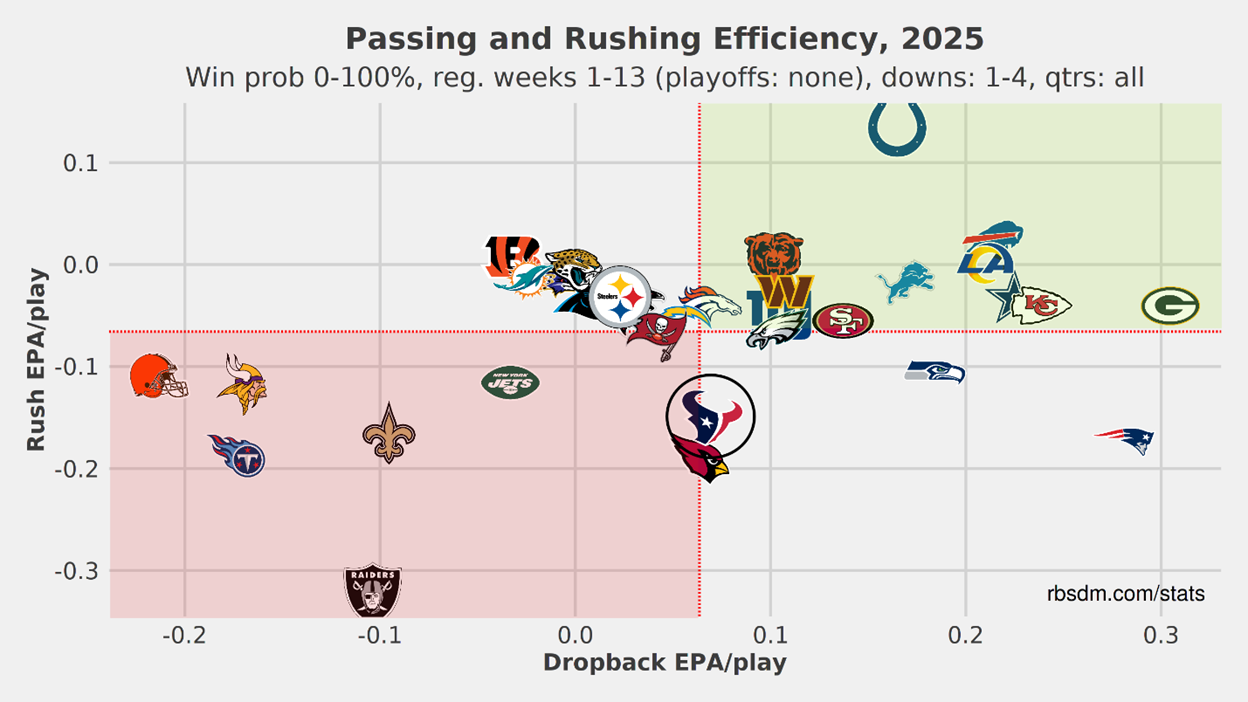

Offensively, the Texans are closer to average in dropback EPA but below average in rush EPA.

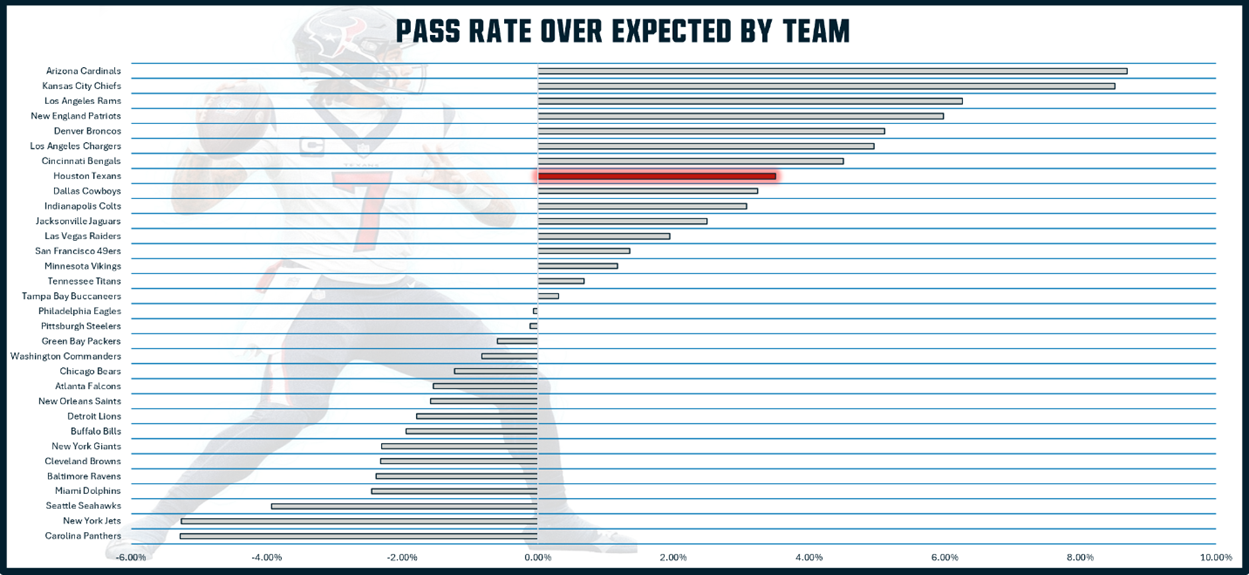

The Texans operate at an average pace, getting offensive plays off at an average rate of 26.8 seconds to snap (T-18th). They throw on 59% of their passes (T-9th). They have a pass rate over expected (PROE) of +3.5% (8th). They average 66 offensive plays per 60 minutes (T-5th).

Houston ranks 21st in offensive EPA per play. They rank 26th in offensive success rate. They rank 15th in offensive EPA per dropback and 17th in offensive success rate on dropbacks.

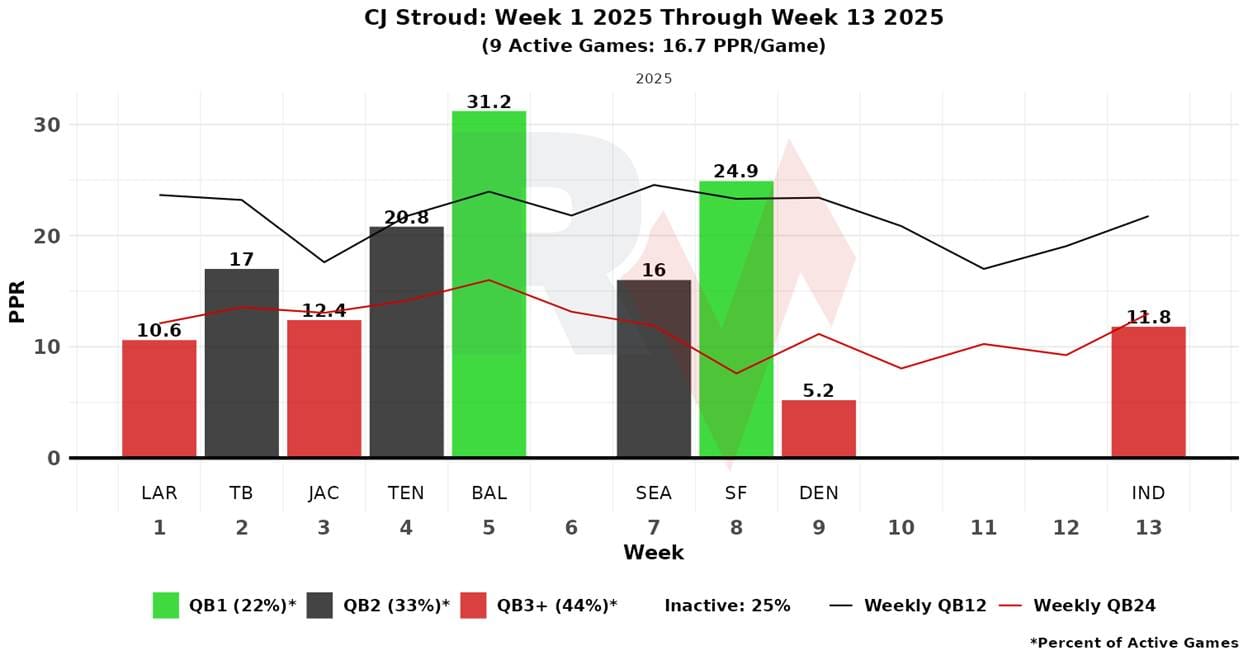

Houston is led by QB C.J. Stroud, who missed weeks 10, 11, and 12. He has dropped back 35.2 times per game (18th) and attempted 30.8 passes per game (22nd). Stroud has rushed for 21 yards per game (15th), so he is a capable rusher, but not an elite one.

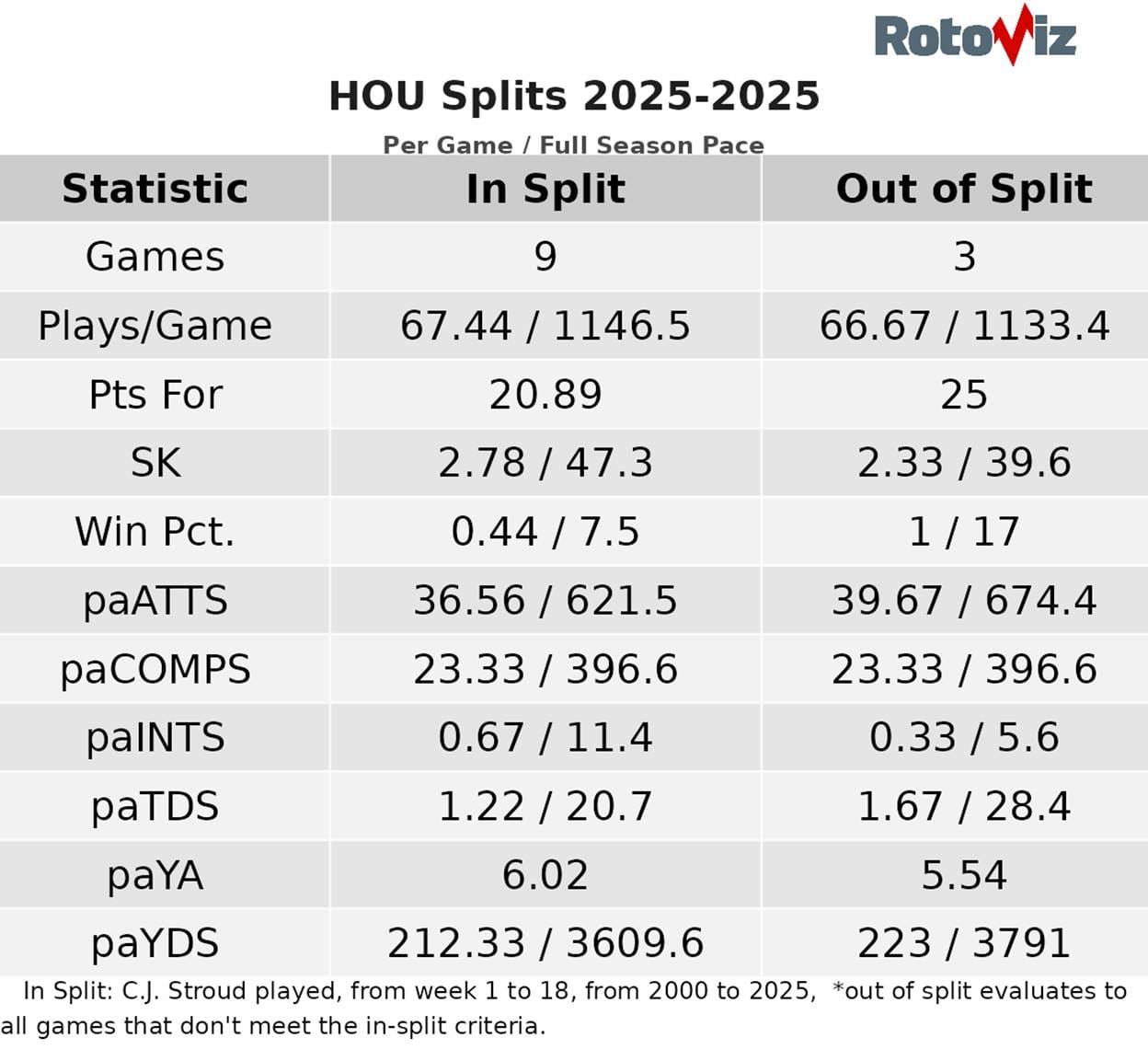

In his absence, Stroud was outperformed by backup QB Davis Mills in almost every way. It is unlikely that, as Stroud has led the Texans to the playoffs in each of his first two seasons, he is in any danger of being benched for Mills, who was the Texans’ starter for two seasons just before that. This is a small sample, as well, but it is interesting to note.

Stroud has been a QB1 twice, including one blow-up game against Baltimore in Week 5. He has been a QB2 three times, and his three other complete-game performances—all falling outside of the top 24—were still passable enough not to tank a fantasy lineup.

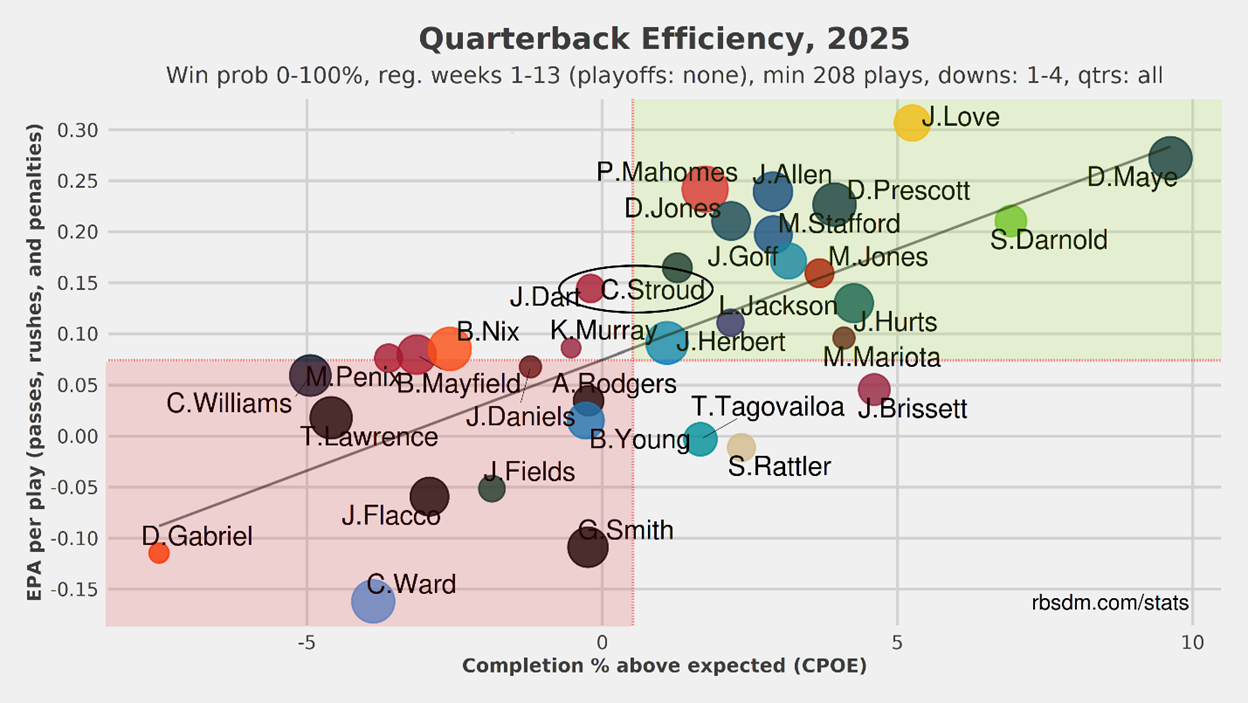

Stroud has been above average in dropback EPA and a little below average in CPOE.

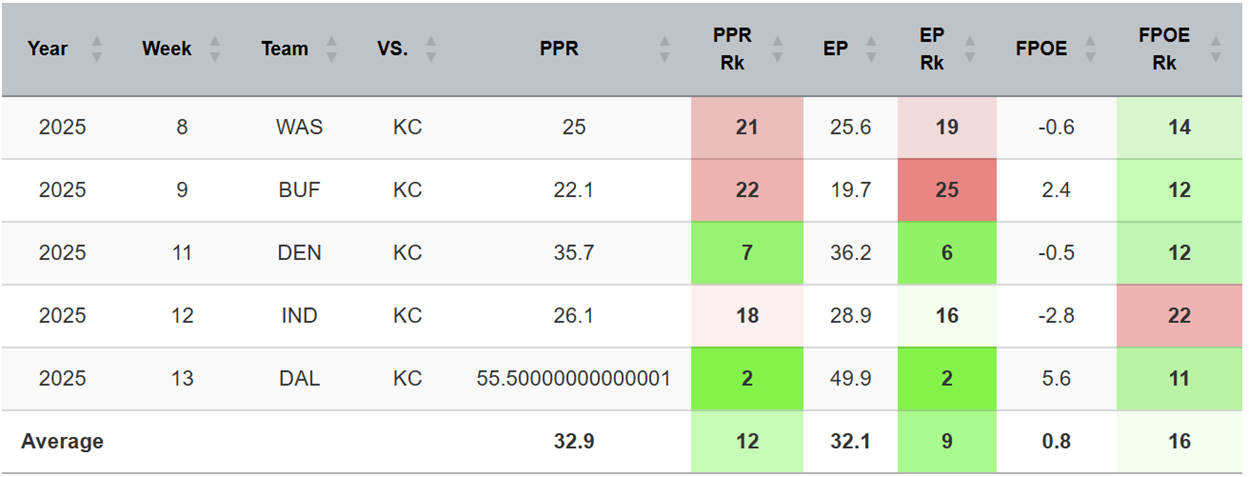

The Chiefs’ defense has been somewhat exploitable by fantasy QBs, as they’ve surrendered the 11th-most fantasy points to opposing signal callers in their last five games. This sample includes Josh Allen, Daniel Jones, and Dak Prescott.

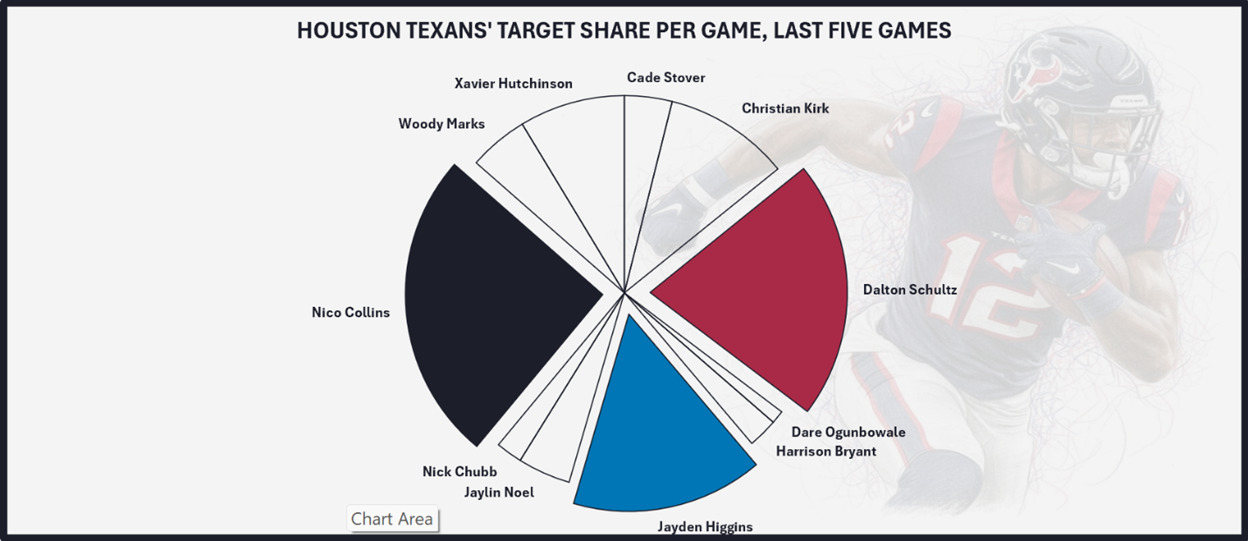

The Texans have three players with a target share per game rate of at least 15% in their last five games: WRs Nico Collins (24.6%) and Jayden Higgins (15.2%), and TE Dalton Schultz (20.4%).

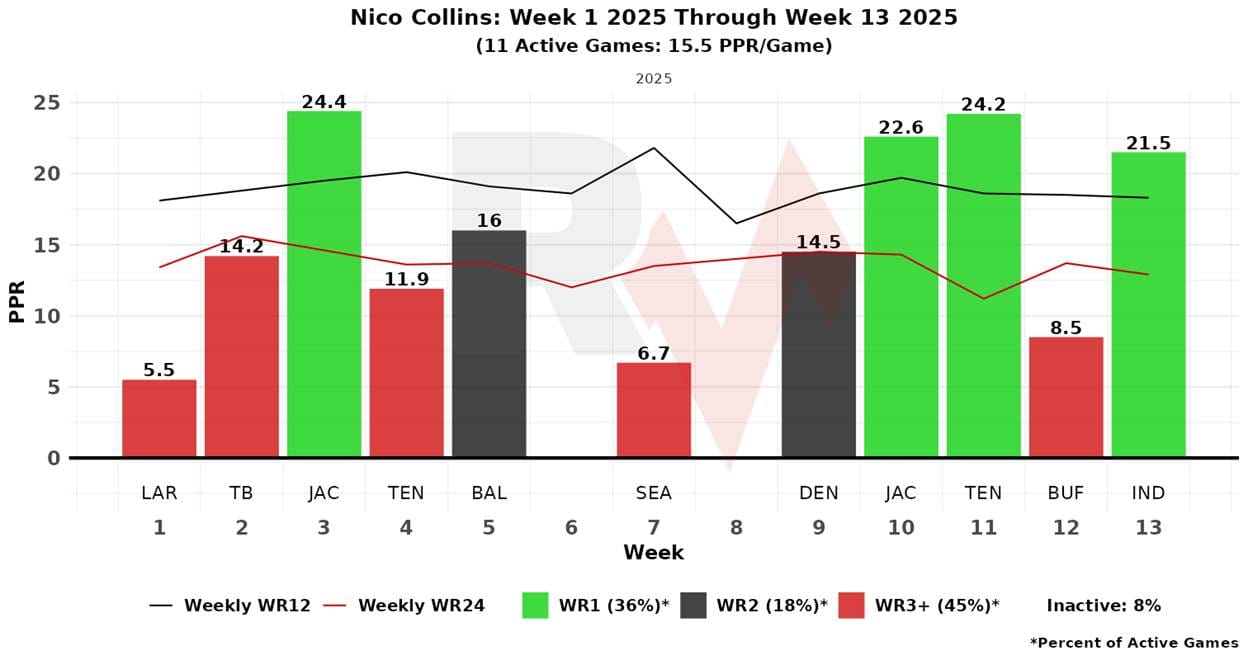

Fantasy GMs drafted Collins to be an alpha this summer; for a while, this was not what they enjoyed, however. In recent weeks, Collins has come on, producing three WR1 outputs in his last three games. Two of these came with Mills under center instead of Stroud, which may be a source of anxiety.

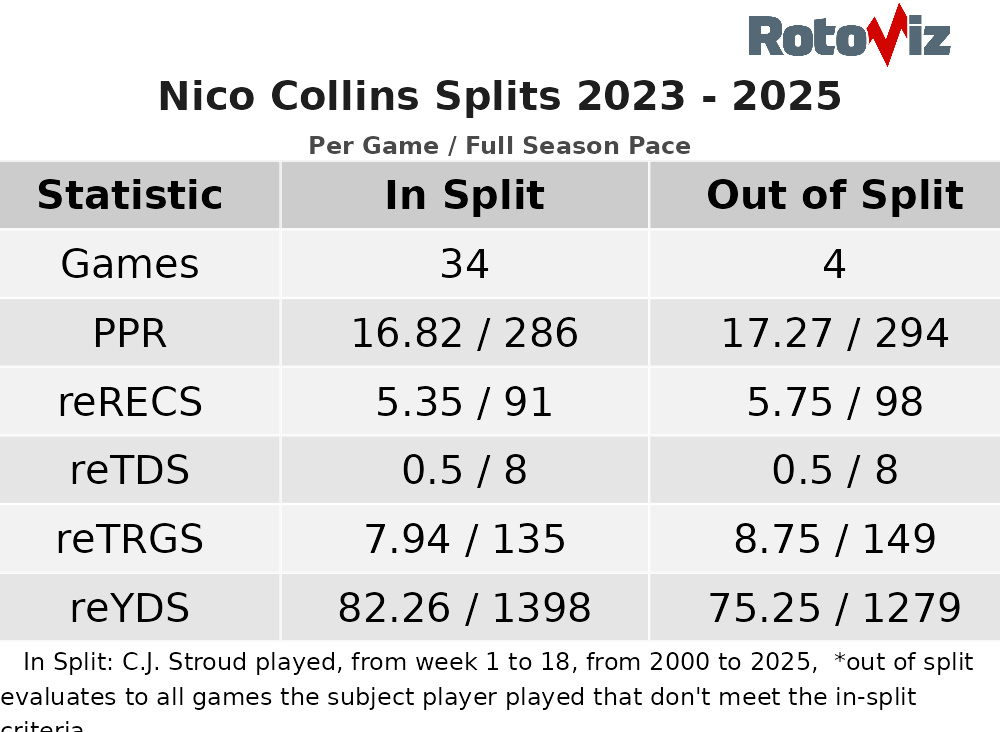

If it is any consolation, Collins has been fantasy's WR7 and WR9 overall in PPR/G over the past two seasons, Stroud was his QB. If the problem with Stroud getting the ball to Collins is not systemic, as we may have feared, given the switch from OC Bobby Slowik to OC Nick Caley, then success with Mills should only alleviate concerns, as it demonstrates that Caley's offense can still support higher outputs. Stroud and Collins have established rapport, even if games with Mills under center slightly outpace them.

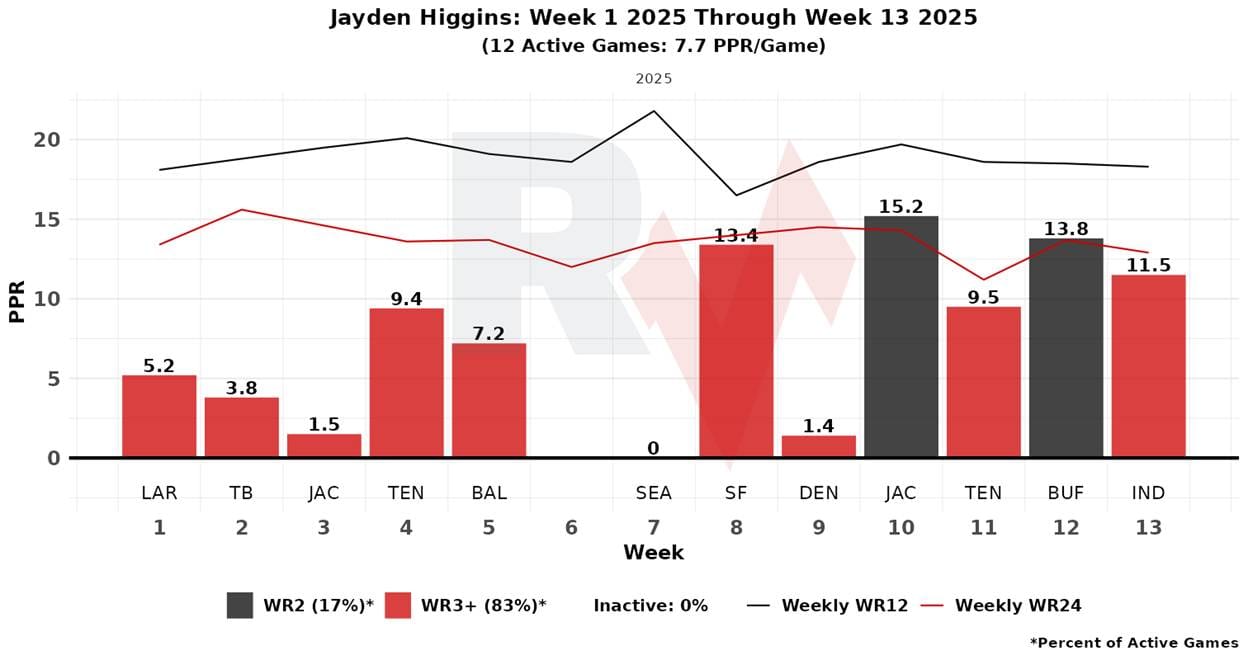

Higgins, a rookie second-round pick out of Iowa State, has had a bifurcated season; the first seven games of his career, he was unusable, but, as we often see with rookies down the homestretch, he’s been on the WR2/WR3 borderline for four of his last five. He still hasn't shown much upside, but he's usable in deep PPR leagues, especially with four teams on bye.

The Chiefs have been vulnerable to WRs in their last five games, surrendering the 12th-most PPR points to opposing WRs during that span.

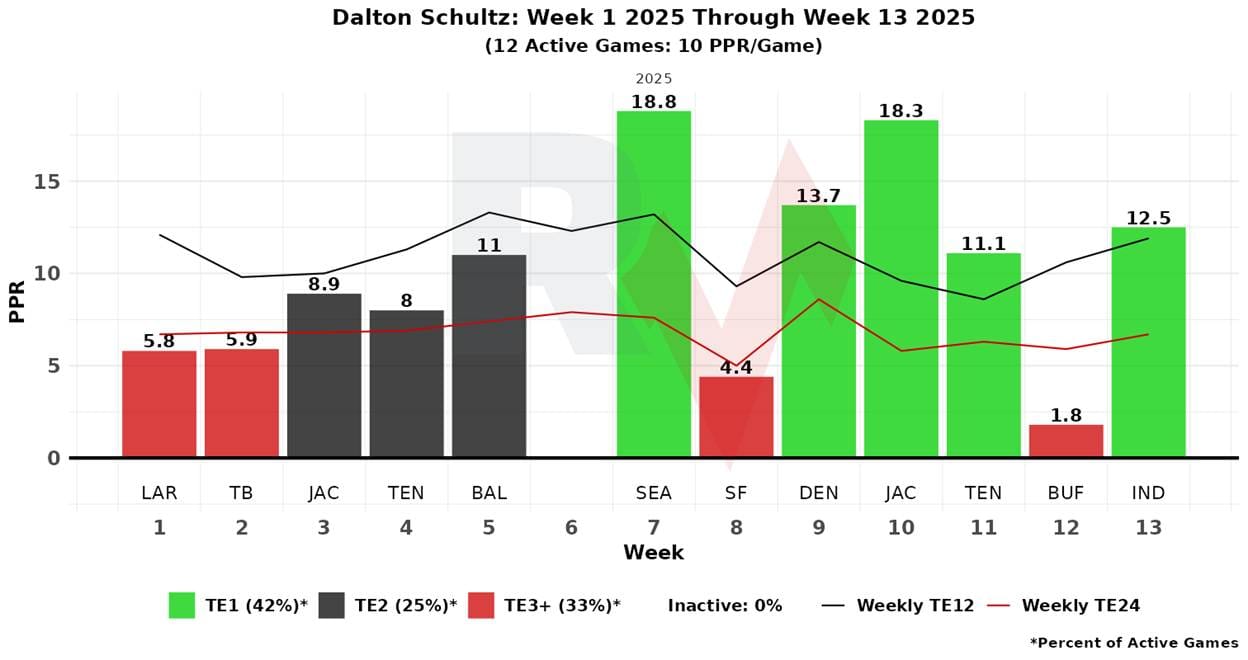

TE Dalton Schultz also had a slow start, but he has picked up the pace and has been the TE5 overall since Week 7, just after the Texans’ idle week. He has been a TE1 five times in his last six games after not finishing the top 12 once before the bye. Two of his best outputs came in complete games by Mills, and a third came when Mills played over half the game against Denver.

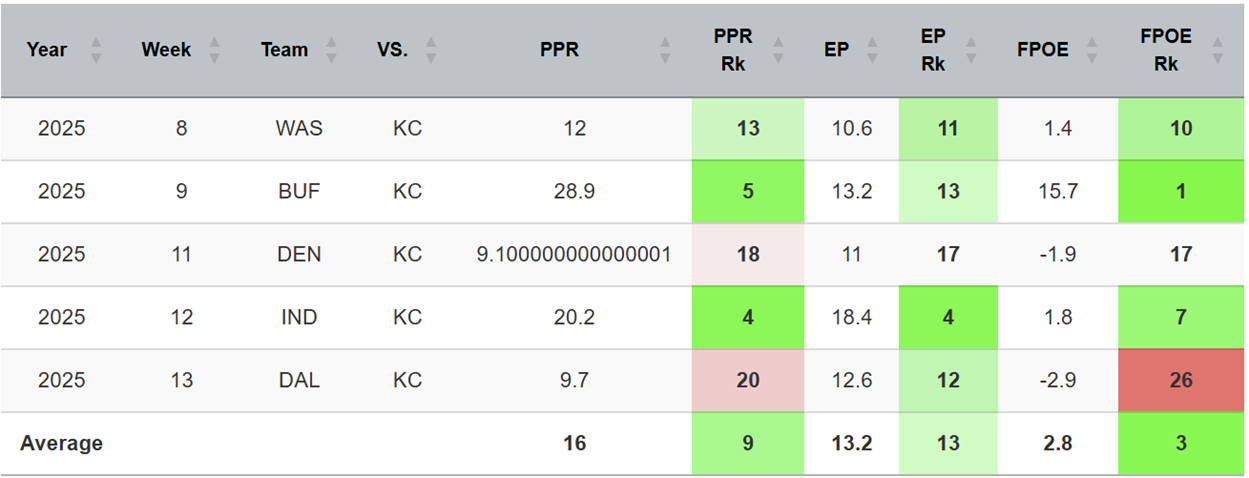

The Chiefs have surrendered the ninth-most fantasy points to TEs in their last five games.

The Chiefs’ defense is slightly below average in pass EPA and rush EPA.

The Chiefs rank 21st in EPA per play allowed and 20th in defensive success rate. They rank 16th in EPA per dropback allowed and 22nd in defensive success rate on dropbacks.

The Chiefs line up in man for 25.8% of their defensive snaps (15th). They use two-high safeties at a rate of 57.5% (3rd). Because they use a wide array of defensive alignments, they only run one alignment more than 20%: Cover 3 (27.0%). They also use Cover 1, Cover 2, and Cover 4 at a rate of over 15%. They blitz at a rate of 31.4% (3rd), and use a Cover zero the most in the league (8.1%).

Fantasy Points’ coverage matchup tool assigns a zero-based matchup grade to each pass-catcher based on their opponent’s use of specific types and rates of coverage and how that pass-catcher performs against them. Positive numbers indicate a favorable matchup and negative numbers indicate an unfavorable one.

Based solely on these parameters, not one single qualified Texans’ WR has a favorable matchup. Collins’ matchup grades out at -9.4%, Higgins’ is at -7.2%. Schultz, on the other hand, has basically a neutral matchup at +0.03%, and is the only qualified pass-catcher for Houston with even a slightly favorable setup.

PFF’s matchup tool is player-based, pitting the PFF ratings of individual players against each other for an expected number of plays based on historical tendencies, then rating them on a scale from great to poor.

Based on these, Schultz and Collins’ matchups grade out as good, while Higgins’ grades out as fair.

Houston allows only a 36.2% pressure rate over expected (PrROE) offensively (10th of 28 Week 14 teams), while Kansas City generates 10.16% PrROE (7th). This is the 18th-worst matchup of the week for the Texans’ offense—not quite neutral, but not overly bad.

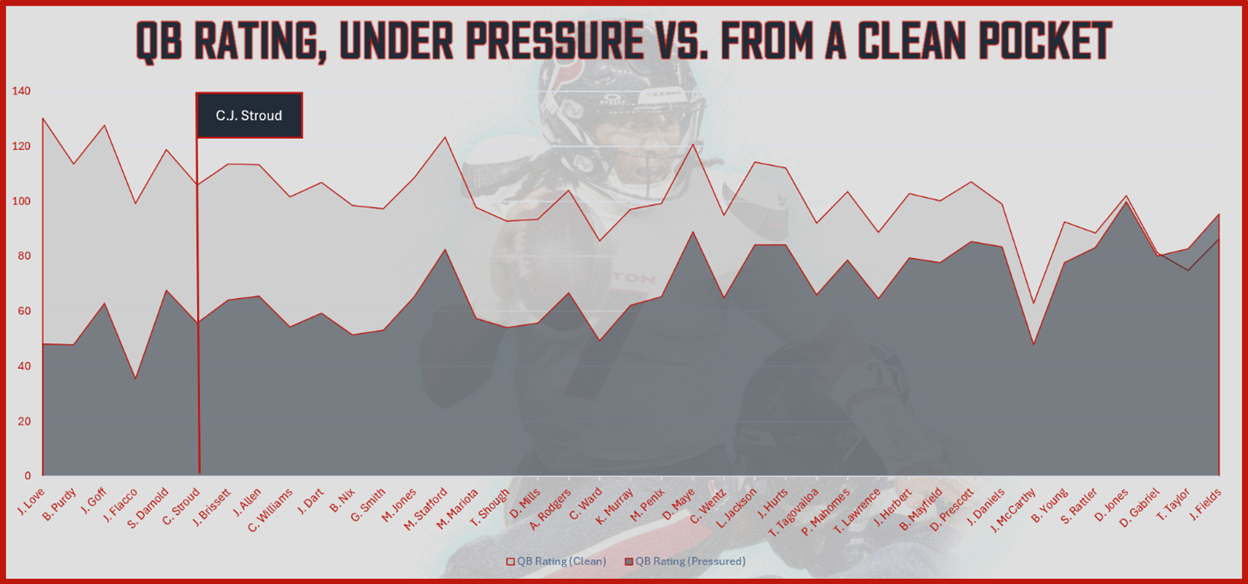

Stroud is far worse as a thrower under pressure, suffering a 50-point drop in QB rating while pressured vs. while kept clean, the sixth-largest drop-off in the league.

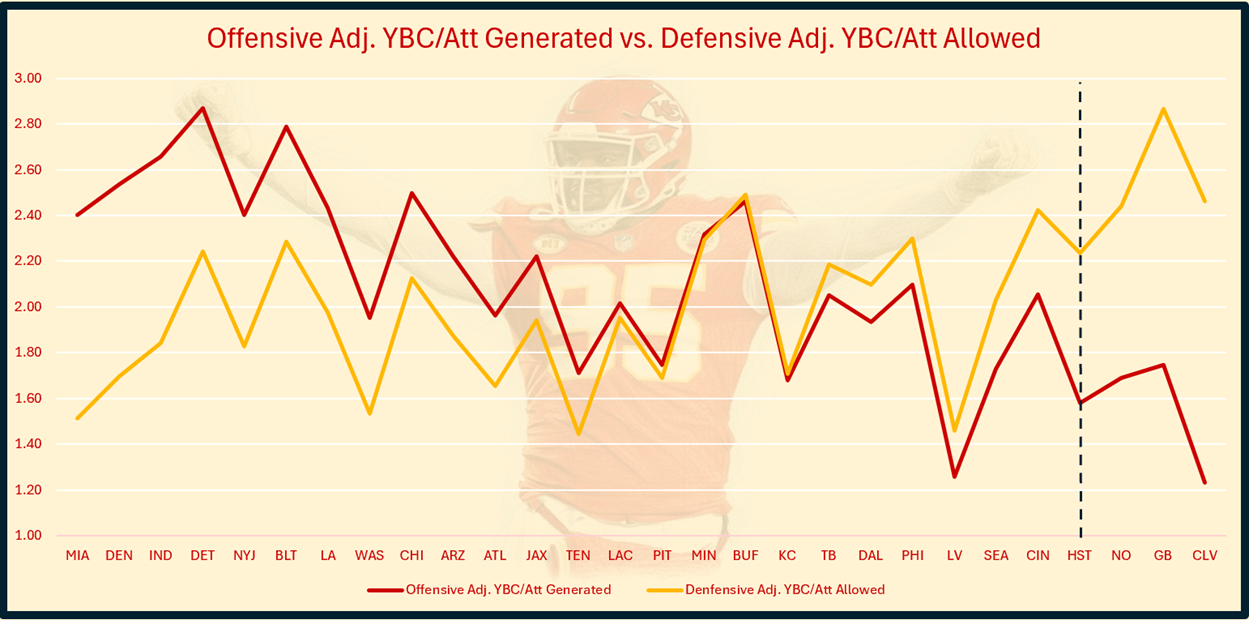

As a rushing offense, it gets far worse for Houston, which generates just 1.58 adjusted yards before contact per attempt (adj. YBC/Att, 26th of 28 Week 14 teams). The Chiefs’ run defense is overrated, and they allow 2.23 adj. YBC/Att (19th), but they still hold the third-biggest advantage of the week against the Texans’ run blocking unit.

The Texans rank 27th in offensive EPA per rush and 28th in offensive success rate on rushes.

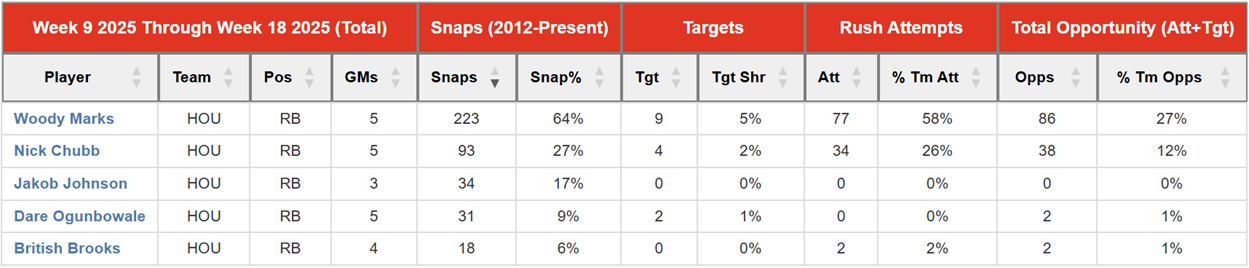

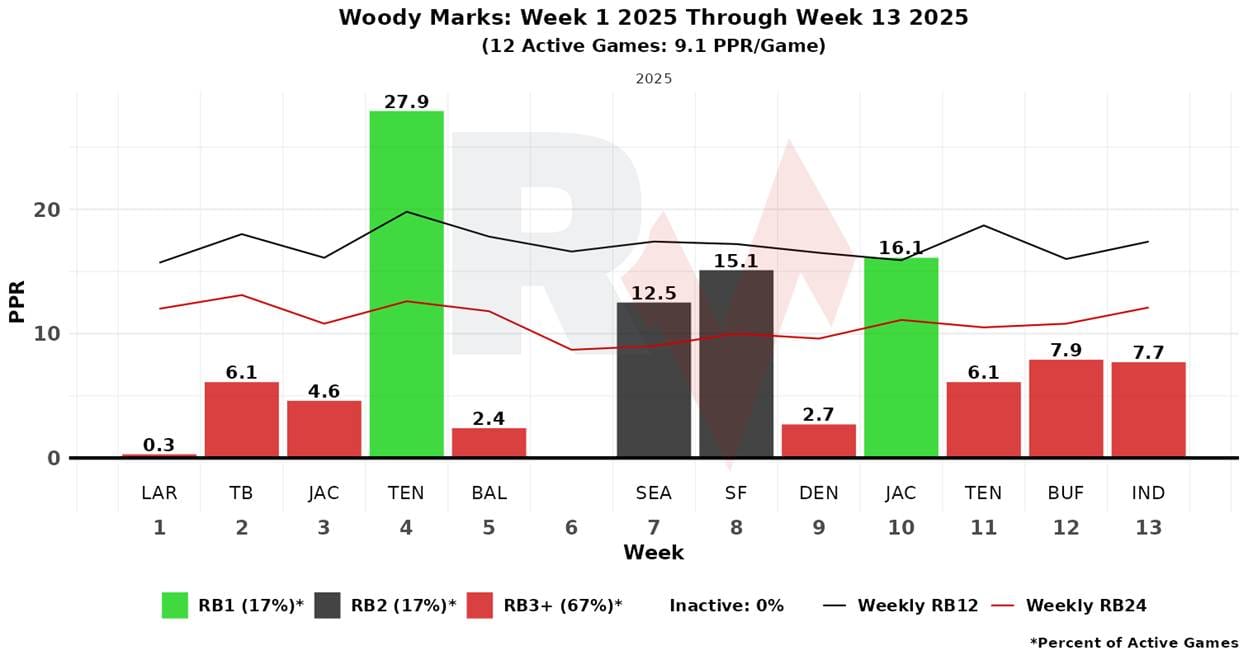

Their backfield has been almost completely turned over to rookie RB Woody Marks at this point; Marks draws 64% of the snaps and 58% of the team’s rush attempts in the Texans’ last five games.

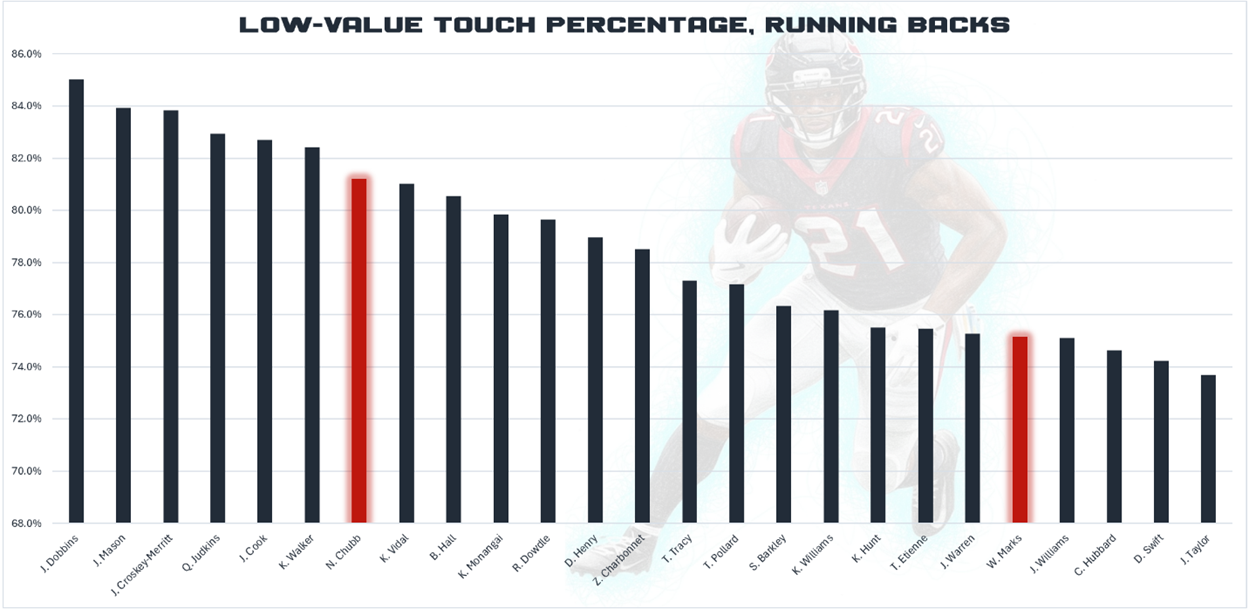

Considering how well he profiled as a pass-catching back in college, it feels utterly strange that Marks is on the field so frequently but is used as a pass-catcher so little. His 5% target share is a non-sequitur; it feels systemic given how Houston would prefer to use their backs on passing downs, but we also know that Marks’ pass-catching profile was probably overcooked by the volume he received with the late Mike Leach during his time at Mississippi State. Since Chubb is still an option near the goal line, Marks is dangerously close to being an RB that specializes in low-value touches, as 75.2% (21st) of his touches are.

As such, anticipating RB1 production from Marks, who has only hit that threshold twice, feels increasingly hopeless. In fact, most weeks, Marks is well below the RB2/RB3 fringe, making him challenging to use for anyone but a zero RB drafter in a deep league who failed to land on a better option along the way.

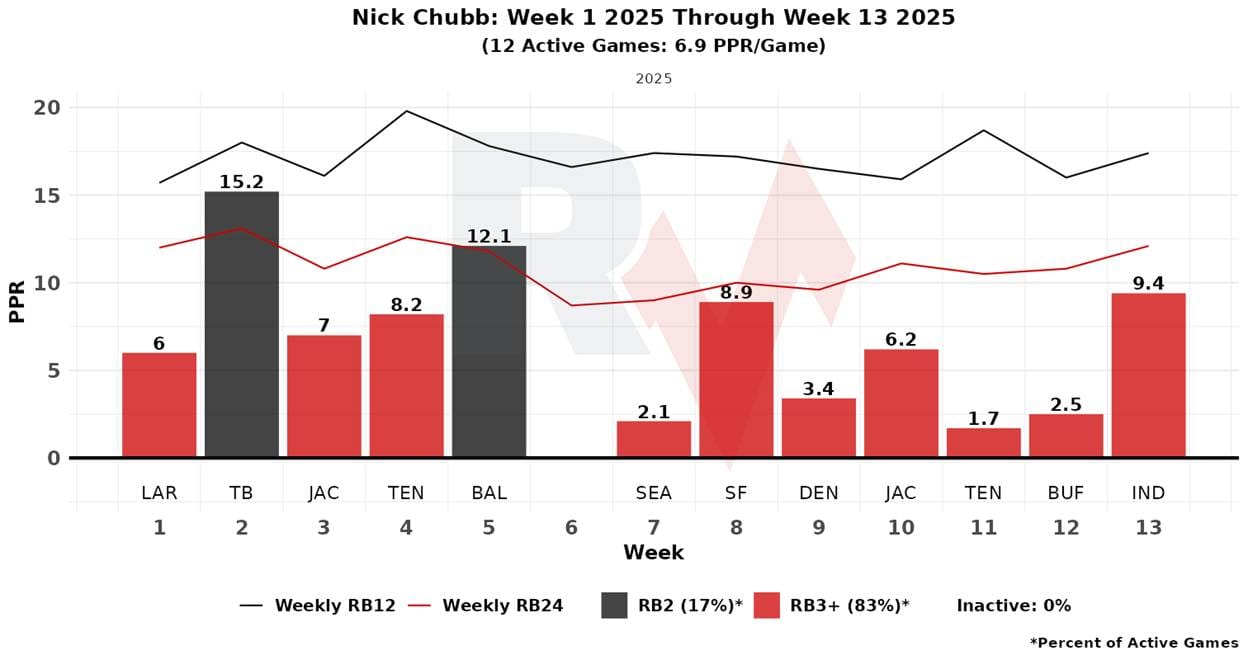

Chubb is even harder to trust; his highs are almost on par with Marks’ lows at this point. Even with a TD last week, he was not able to crack the top 24.

Chubb’s low-value touch percentage is even higher at 81.2% (7th). He is practically unusable and likely droppable almost anywhere.

The Chiefs rank 22nd in EPA per rush allowed and 17th in defensive success rate on rushes.

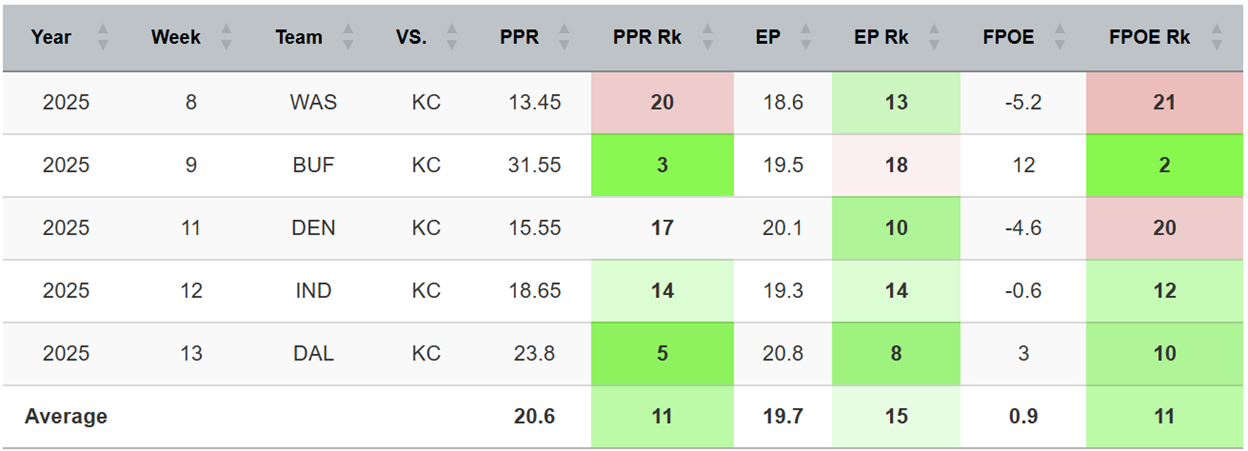

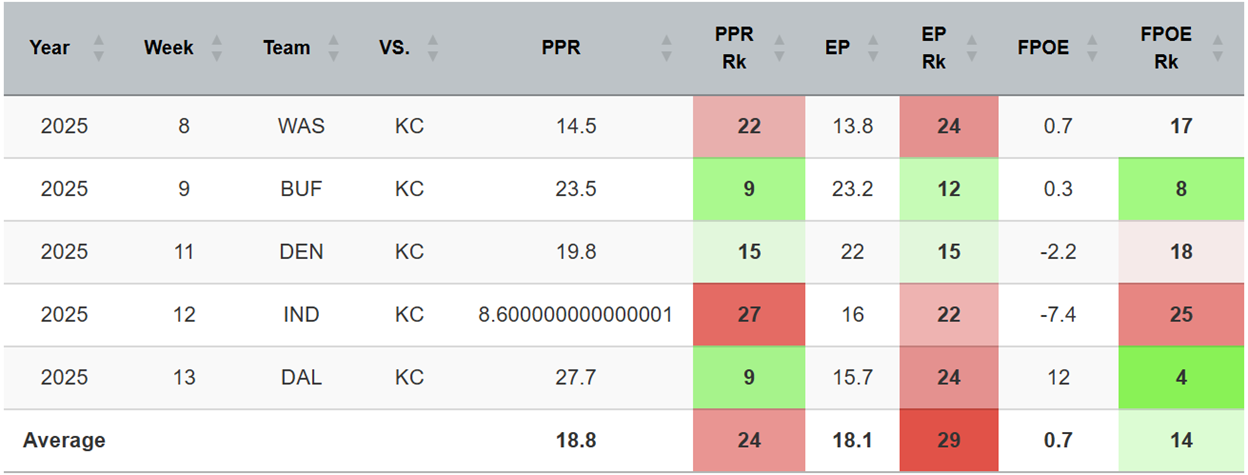

Despite this, they’ve held opposing RBs to the 24th-most PPR points. This feels like a contradiction, and the temptation is to assume the Chiefs’ rush defense is better than it is, particularly given their prowess in recent seasons. However, if we examine closely, we see that the expected points (EP) the Chiefs have allowed rank 29th, while their fantasy points over expected (FPOE) rank 14th.

This indicates that teams have not tested the Chiefs as often, but when they have, the Chiefs’ defense has largely failed. Considering the Chiefs have not spent a large amount of plays ahead by seven or more (194, 12th), this seems kind of real. That said, their Week 12 performance against Jonathan Taylor, one of the best RBs in the NFL, was undeniably impressive and demands our attention.

Either way, the Texans don’t have the horses to mount a massive concern for Kansas City in run defense. While teams like to exploit other teams’ weaknesses, they also naturally want to play to their own strengths, so I don’t expect the Texans to prioritize establishing Marks or Chubb unless they find early success with it.